Project Description

Background

At age 49 and counting, Electric Lady is one of the world’s first artist owned recording studios and one of the oldest, most famous and most successful studios ever. WSDG co-founder John Storyk was a 22-year-old fledgling architect fresh out of Princeton University when he was hired to design a studio for Jimi Hendrix. One summer evening in 1968, Storyk was enjoying an ice cream cone and leafing through the Village Voice when a classified ad caught his eye: “Carpenters wanted to work for free on experimental nightclub.” Dialing the number from a corner pay phone, he got the gig.

Fast-forward three months… After volunteering some creative design suggestions, Storyk was promoted from unpaid volunteer carpenter to unpaid volunteer architect. He quickly put his nascent architectural stamp on ‘Cerebrum,’ which instantly attained “Hot Club Of The Hour’ status. Its look, crowd, location and timing were impeccable. It was the dawn of Soho, a Greenwich Village neighborhood of old loft buildings fast becoming a magnate for artists, musicians, and journalists. Attracting a super cool crowd from the get go, Cerebrum took off for the stratosphere after its unique (early Storyk) design and hip fan base won it a cover of Life Magazine. One night, Jimi Hendrix dropped in and was blown away by its unusual design.

Coincidentally Hendrix and his manager, Michael Jeffrey, were planning to open a club of their own and had already bought a property on 8th Street. Generation, the existing club was a mildly successful blues club in the basement of a small Greenwich Village movie theater which had been designed by Frederick Keisler, an obscure sculptor/ architect, whose gracefully curved, Bauhaus-style work had (coincidentally), been a major influence on Storyk’s creative thinking. An aspiring blues musician, as well as a fledgling architect, Storyk already knew the space. Though unaware of its ‘Keisler connection’, he had been a frequent patron of Generation, stopping in to catch performances by Buddy Guy, Junior Wells and occasionally Hendrix himself before he attained superstar status.

Hendrix had been so impressed with its Cerebrum’s design that he wanted the same architect to design his club. His manager tracked John down in the winter of 1969 and they quickly decided they wanted to work together on the Generation renovation. It took Storyk a couple of months to design the club. Construction began in the early spring, and was proceeding smoothly until a sudden change in plan stopped everything cold. Jim Marron, who had been hired to run the new Hendrix club, somehow determined that it wouldn’t be successful in that location. Instead, he convinced Hendrix to build a personal recording studio in that basement site. And, Marron recommended that Jimi’s young, South African, producer/engineer, Eddie Kramer, be hired as the principal consultant to the reformulated project.

Storyk, now a 23-year-old, fledgling architect was fired as the club designer. “No problem,” he said, “I’ll design the studio instead.” A crash course internship with industrial acoustician Bob Hansen, who had been hired to develop the isolation details for the studio, provided Storyk with an ‘on the job training’ course in acoustics. By late May of 1969, he had completed the drawings for Electric Lady Studios. Jim Marron was named the studio’s first manager. Eddie Kramer went on to engineer virtually all of Jimi Hendrix’s recordings, and soon become one of the industry’s most acclaimed producer/ engineers, with credits for artists ranging from The Beatles to David Bowie and Eric Clapton.

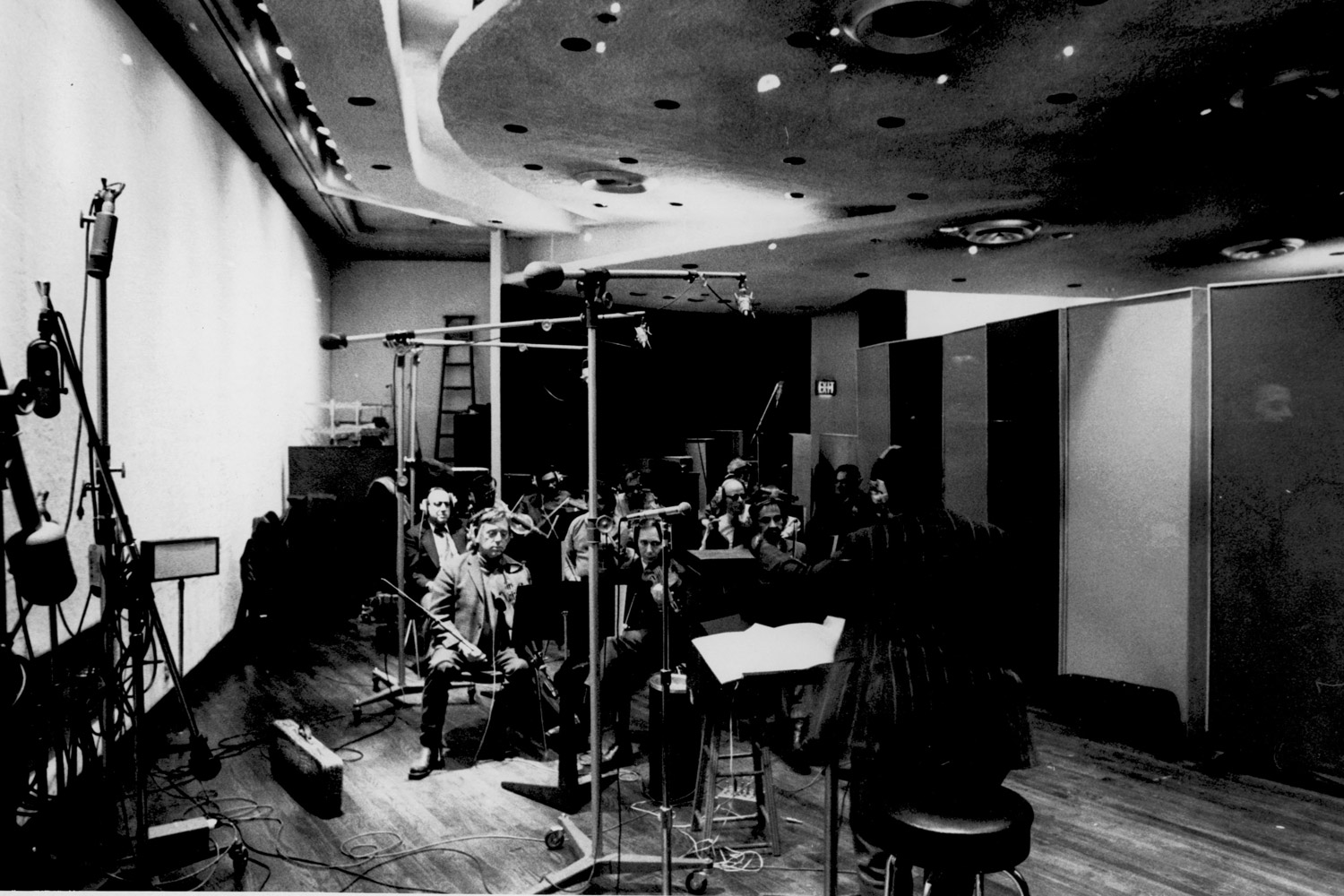

Program Requirements

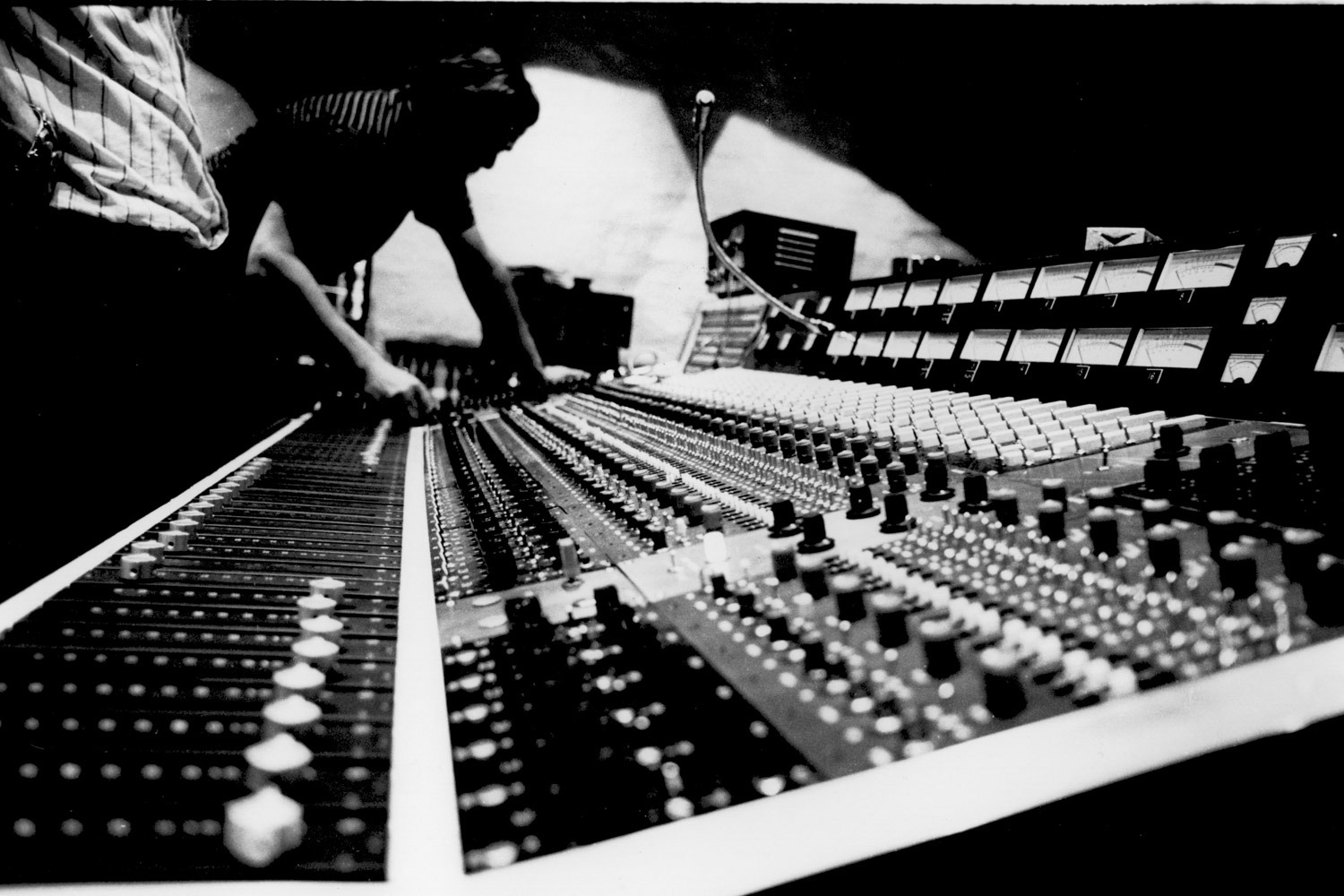

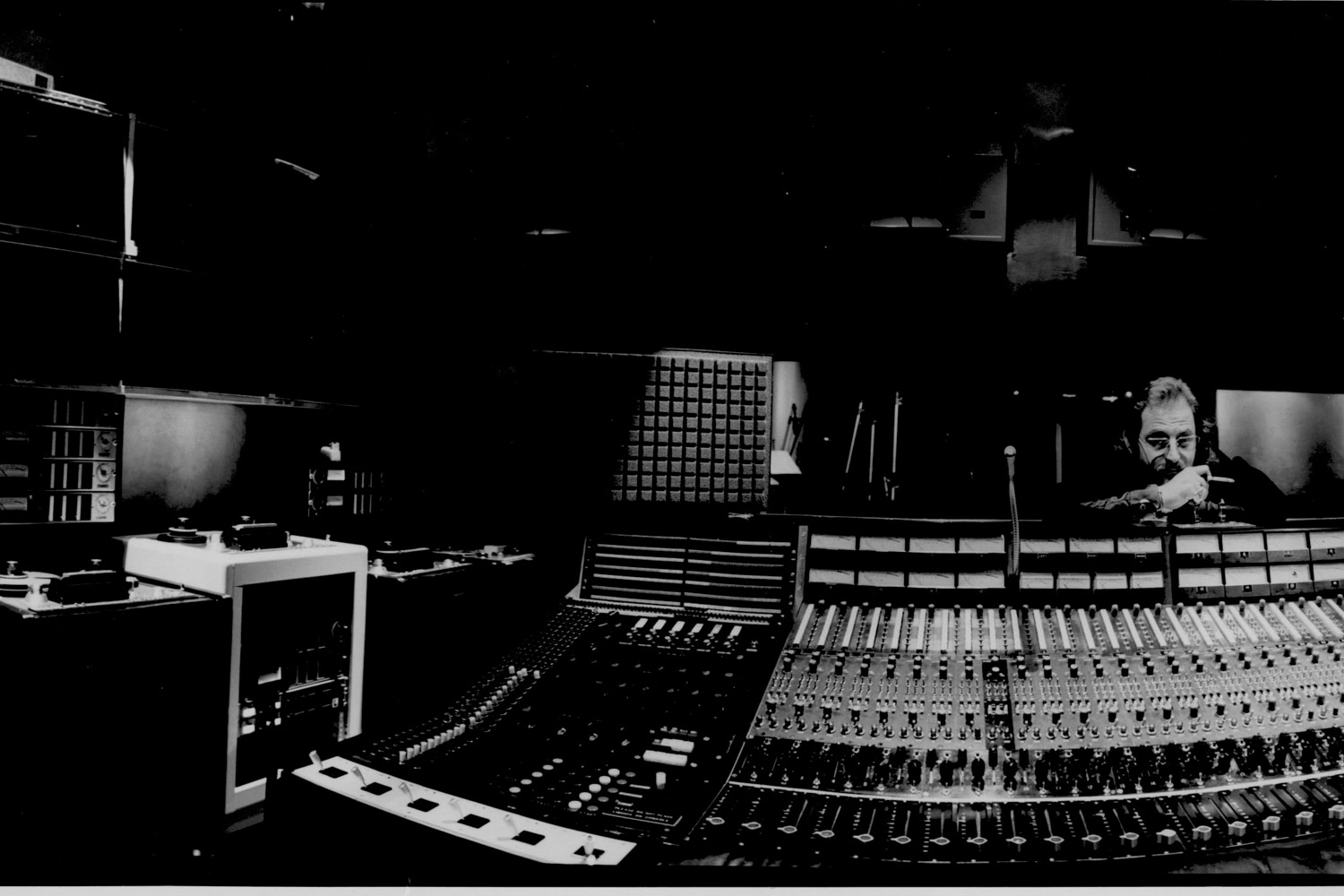

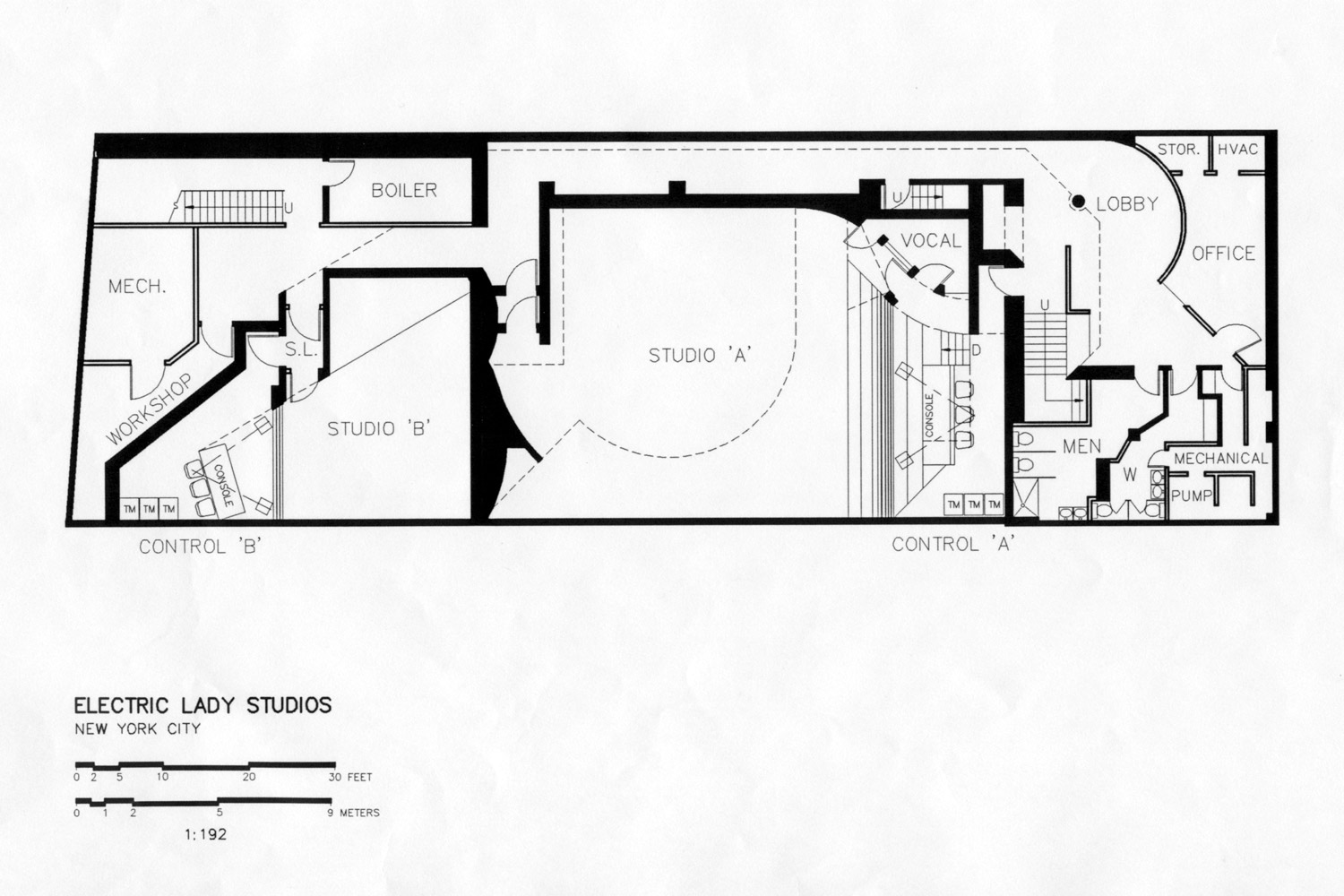

Kramer was adamant about Electric Lady having a tall, bright room similar to NY’s legendary A&R Studios where Phil Spector did some of his greatest work. Kramer was also familiar with European studios like London’s Olympic and Abbey Road. He believed drums required a big room. Storyk accommodated Kramer’s need for high ceilings by excavating the basement, digging down to raise the height of the underground rooms. For the studios interior, Jimi specified theatrical lighting, and his desire to have as many curved surfaces as possible (design elements which Storyk had originally incorporated in Cerebrum). Electric Lady’s walls were painted white, so they could easily be turned into whatever color Hendrix was in the mood for with simple adjustments. One day Jimi arrived at the construction site and decided that he didn’t like the square look of the expensive acoustic doors, which had just been installed. He asked Storyk if he could round off the tops, and when that proved impractical, he had them replaced by custom units with rounded, porthole-style windows.

Electric Lady took nine months to build. The ‘floating’ completion date was partially due to stops and starts that reflected Jimi’s erratic touring and record sales income; and partially caused by other eleventh hour design changes. Yet another totally unexpected ‘floating’ delay was triggered by the Minetta Brook, an active stream, which ran through the primordial forest which stood for eons on Manhattan Island, before the Indians, the Pilgrims, the rock stars and the hippies gravitated to what eventually became Greenwich Village. To resolve the running water problem, Storyk had to modify the design, essentially back-filling one of the walls, and shifting from block to stud construction to provide sufficient load support. Additional room also had to be carved beneath the studio floor to accommodate a pair of water pumps installed to eliminate occasional floods when the stream ran over its banks, a situation that persists to this day.

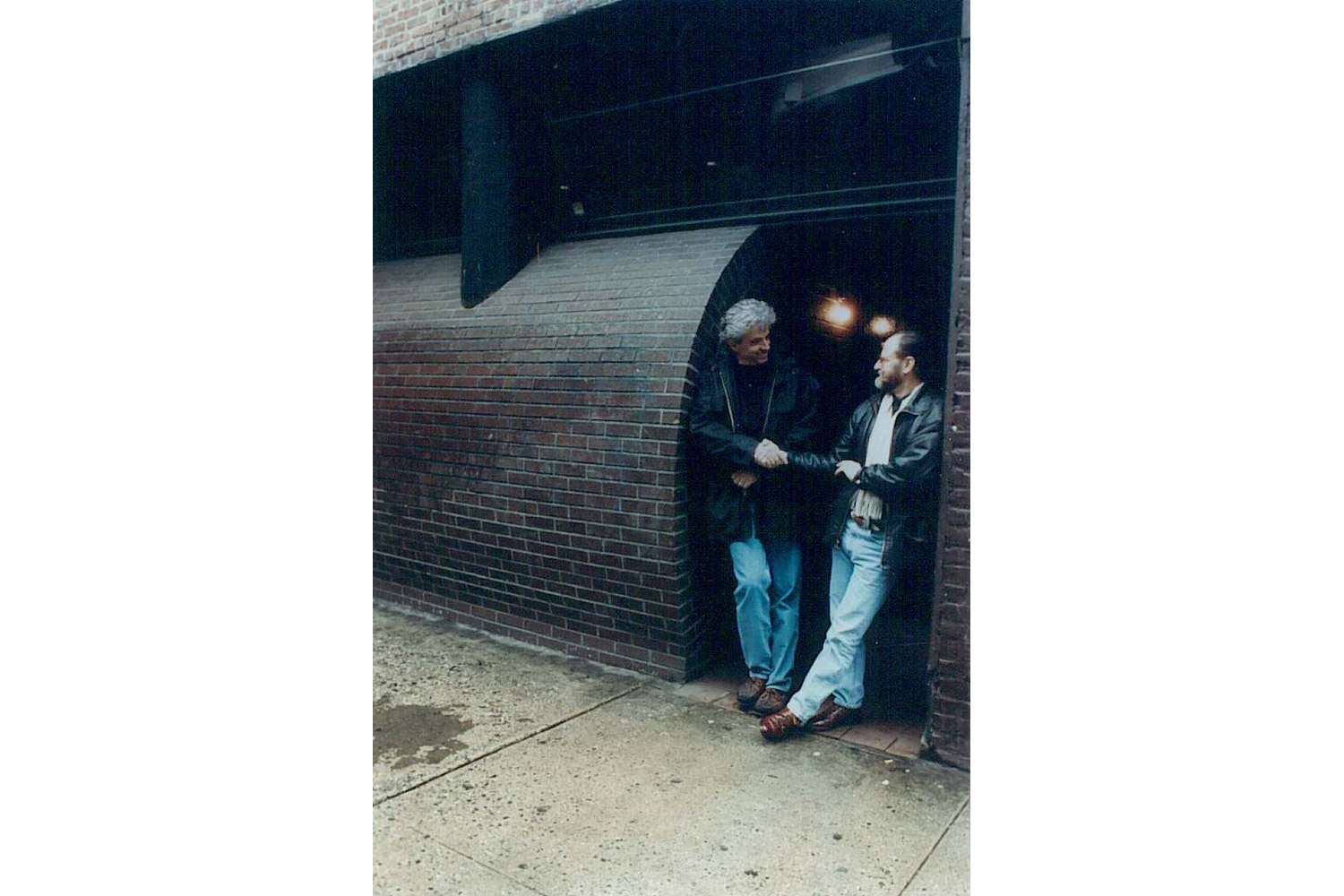

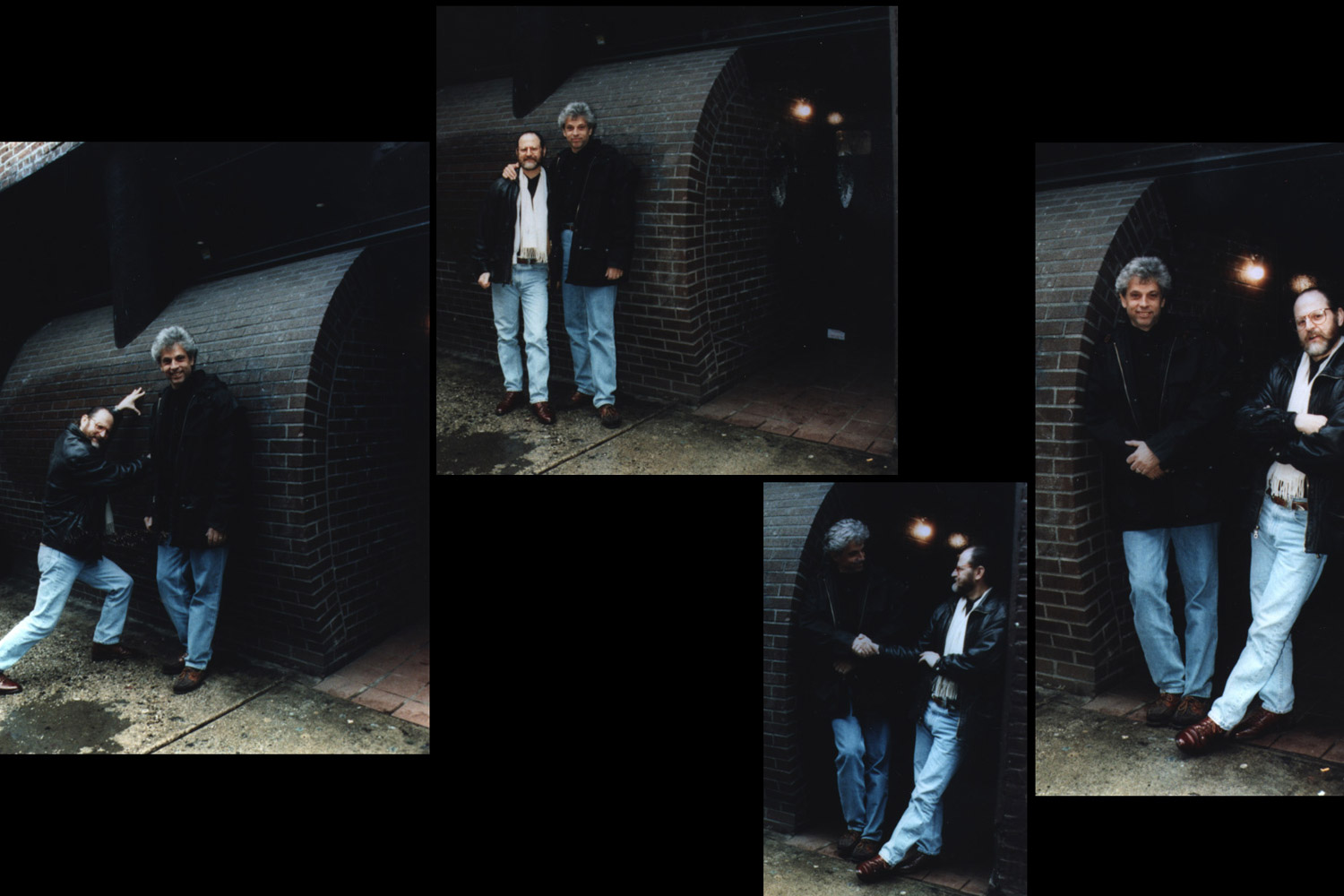

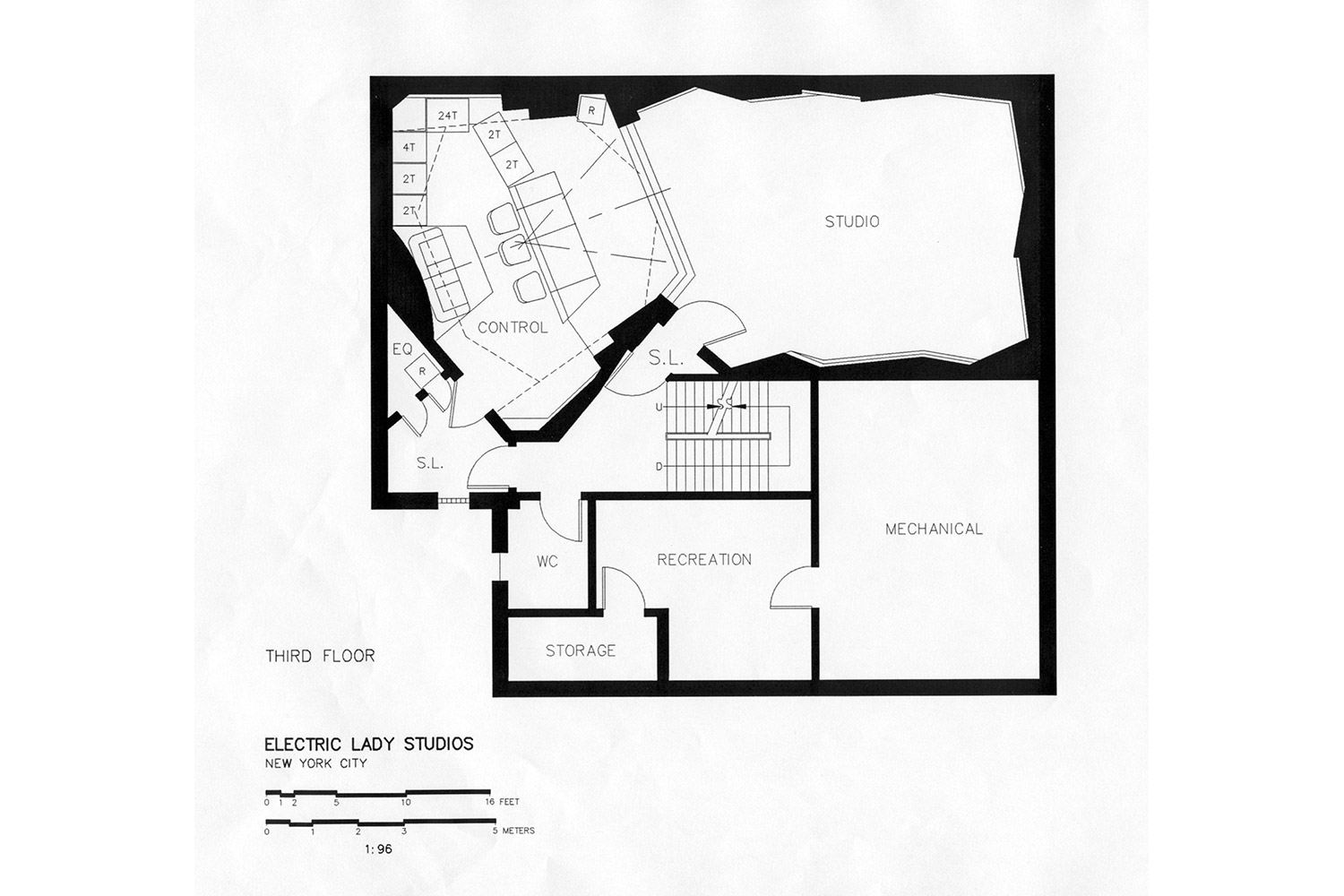

Recording consoles, speakers and other technology have been updated over the years to address the needs of a constantly changing recording industry. WSDG is still engaged occasionally by Electric Lady for periodic acoustical fine-tuning. We have designed an upstairs mix room and upgraded and reconfigure the live and control rooms. However, many Electric Lady have remained unchanged. On the upside, the psychedelic sci-fi themed mural painted by Artist, Lance Jost continues to grace the long narrow hallway leading to Studio 1. On the downside, in 1997, the studio’s massive, iconic, curved red brick, street-level entrance, was demolished by the landlord. “And why?” You ask. To gain one foot of additional space, for a neighboring store. Ironically, John Storyk and Eddie Kramer posed for a photo in front of Electric Lady just two weeks before it was destroyed. Hope spring eternal that the curved wall may someday be restored.

What is it that makes Electric Lady so special? To begin with, artists in 1968 simply didn’t have their own studios – not even The Beatles wanted to go to the expense of building and maintaining such a complex environment. Yachts and jet planes yes, studios, not so much. The artist-owned studio was a renegade concept pioneered by Jimi Hendrix in his quest for creative innovation and independence. Hendrix lore and the countless superstars who have recorded Gold and Platinum hits at Electric Lady continue to lure contemporary artists. From The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, U2 and Stevie Wonder to Arcade Fire, Beck, Daft Punk and Lana Del Rey, ELS remains a beacon of music recording’s past AND future.

“Lastly,” John Storyk concludes, “Jimi can rest easy in the knowledge that his Electric Lady is in good hands. Studio manager Lee Foster came on board ten years ago while he was still in his twenties. He’s made the studio’s survival a personal mission, and he’s doing a terrific job of keeping it in pristine shape, technically and aesthetically. No one comes to a recording studio because of its legend. They come because they know the music they record there will sound exactly the way they want it to. They trust Electric Lady. It’s not a museum; it’s a great studio. And they count on Lee Foster to keep it that way.”

Testimonial

Lee Foster | Electric Lady Studios

Studio Manager

“I am very, very fond of John–to me, he’s family. I’ll never forget him because as a young man stepping into all of this, he would always pick up the phone or be willing to come down and talk to me about things—his guidance has been extremely important. Now we talk all the time.”

Links

Read The Wall Street Journal Article

Read Audio Media International Article

See audio Timeline – 1970 in Fast-and-Wide (03/15/2013)

Read TV Technology Article (12/20/10)

Read The New York Times Article

Read Pro Sound News – Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition” Article (10/07/10)

Read Pro Sound News Artcle (8/30/10)

Read Poughkeepsie Journal Article (12/14/06)

Read Professional Sound cover story (7/15/08)

Read the Rolling Stone review of “Valleys of Neptune” (released 3/9/10)

Click Here for a PDF of the article ‘Jimi’s Last Ride’ published in Rolling Stone, April 2010 (16mb)

Click Here for a PDF of the article in Recording (1/21/12)

Read the AirMail Article (11/19/22)

Click Here to Listen to the Interview on WNYC