Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios was in danger of closing, until the arrival of Lee Foster. Now it celebrates its 45th anniversary with a concert series kicked off by Patti Smith

Electric Lady Studios co-owner Lee Foster with Patti Smith, who first recorded there in 1974. ‘I love the atmosphere of the studio,’ she says. ‘It’s someplace I feel a sense of continuity.’ PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIO SORRENTI FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

Electric Lady Studios co-owner Lee Foster with Patti Smith, who first recorded there in 1974. ‘I love the atmosphere of the studio,’ she says. ‘It’s someplace I feel a sense of continuity.’ PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIO SORRENTI FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

ON AUGUST 26, 1970, Jimi Hendrix threw open the doors to Electric Lady Studios, his Greenwich Village recording studio, to a group of musicians and friends. Named for the Jimi Hendrix Experience album Electric Ladyland, the studio looked like a New Orleans pleasure house embedded in a psychedelic space capsule. Patti Smith was at the opening party, along with Ronnie Wood, Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood; all would go on to record there. Hendrix saw Smith sitting on the steps that night, like a “hick wallflower,” she wrote in her memoir Just Kids, and told her he wanted Electric Lady to be a place where artists of all kinds would record the “abstract universal language of music.” Three weeks later, Hendrix died in a London apartment after ingesting an excess of barbiturates. He was 27 years old.

Miraculously, his vision survived him: From its inception, his mother ship served as a rock, funk, disco and soul Olympus where gold and platinum hits were forged. In the ’70s, Led Zeppelin, Stevie Wonder, Lou Reed, the Rolling Stones and Blondie all recorded there. It was Electric Lady where two members of a raw, young band called Wicked Lester laid down demos in 1971; they would return as Kiss to record Dressed to Kill. In 1975, John Lennon and David Bowie strolled in and improvised the number-one single “Fame,” for Bowie’s Young Americans album. That same year, Smith recorded her first album, Horses,there; and a couple of years later, Nile Rodgers arrived with his band Chic and recorded the multiplatinum single “Le Freak.” The enchantment held through the ’80s and ’90s, as AC/DC and the Clash showed up, then Billy Idol, the Cars, Weezer and Santana. The house that Jimi built welcomed them all.

Forty-five years later, Electric Lady still stands. Its block of West 8th Street now houses a medical clinic, a frozen yogurt shop and a Goodwill store. But keen-eyed observers will spot a groovy, oval-mirrored door tucked amid the workaday storefronts, a glass wall with silvery bubble letters bearing the studio’s name and, behind it, dark velvet curtains. Within, the Lady’s multigenerational family rocks on, recording, mixing, performing or frolicking on the roof at barbecues. Open any door in the past five years, and you might have seen Daft Punk laying down tracks forRandom Access Memories (winner of the 2013 Grammy for album of the year), Bono and Adele chatting with interns, or Jay Z and the Edge dancing with an engineer’s mom. U2 took over the top floor to cut their latest album, Songs of Innocence; Keith Richards came in to record an expanded version of Some Girls in 2011 (in July, he chose the studio as the place to give a first listen to his new solo album, Crosseyed Heart). The star British mixing engineer Tom Elmhirst has taken up permanent residence in Studio C, where last year he mixed Beck’s Morning Phase, winner of the 2014 Grammy for album of the year. On one day last winter, seven sessions proceeded simultaneously, including: Interpol in Studio A; Jon Batiste (the bandleader for The Late Show with Stephen Colbert) in Studio B’s live room; and Lana Del Rey, Rod Stewart and producer and singer-guitarist Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys all working on the third floor. “This place is a beating heart; it’s got its own rhythm,” says Elmhirst.

Yet only a little over a decade ago, the Lady nearly vanished. The music industry was in a downward spiral, the studio’s infrastructure was deteriorating, and 10 months went by without a single booking. “The place was almost on its back,” remembers the architectJohn Storyk, who was 22 when he designed the studio in 1969 (it was his second official commission; Hendrix took a chance on him, impressed by a Soho nightclub Storyk had designed called Cerebrum). Mark Ronson, who frequented the studio at the turn of the millennium, during the “soulquarian” period, when the Roots, D’Angelo and Erykah Badu recorded there, thought its “glory-days era had sort of ended.” Hendrix’s estate had sold the studio in 1977, and it changed hands again, in 2004. The owners thought they’d have to close it down.

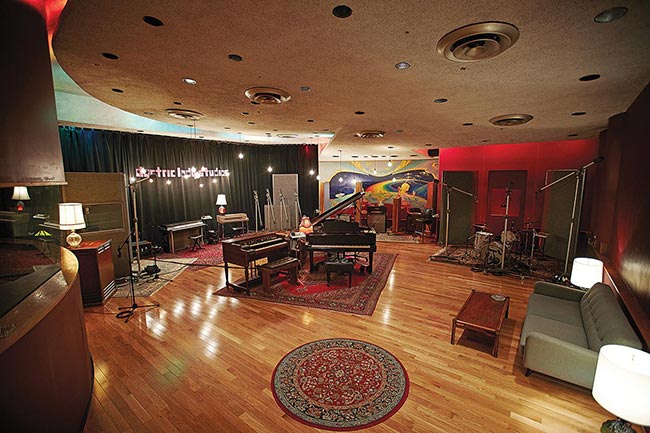

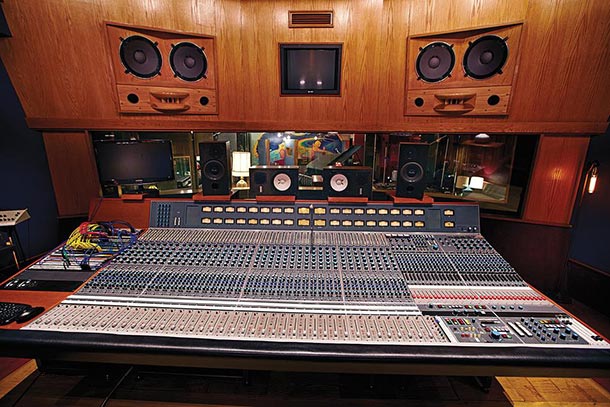

One freezing New York night in February, a gaggle of partygoers were buzzed into the studio for a party to toast Electric Lady’s legacy. Descending a steep staircase, they emerged into an underground parlor with Persian carpets, Chesterfield sofas, fringed lamps and, everywhere you looked, speakers, consoles and recording equipment. A mural painted by the California artist Lance Jost curved around the subterranean walls, depicting an intergalactic spacecraft where blond astronymphs perched by broad windows, admiring the floating universe. This was the fabled Studio A—which looks virtually the same as it did back in the day, says Storyk. A wiry, tattooed guy in a knit cap and cowboy boots broke the nostalgic spell as he started to address the crowd. For a moment, he looked like Pinkman, Aaron Paul’s character in Breaking Bad, or, on second glance, a sound engineer, about to say, “Check, check….” But then he began speaking, in earnest, Southern-inflected tones. His name, he said, was Lee Foster. He was from Tennessee; and as he described the transformation of the studio over the past 10 years—the resuscitation of moldering floorboards and dated equipment and the slow return of the rock pantheon—it became clear that he was the protector of this monument to music’s golden age. “I will say this without a doubt,” says Eric Kaplan, counsel to the family who gave Foster the reins in 2005 (and who have always retained anonymity). “Without Lee Foster, Electric Lady would have died.” Since 2010, Foster has been the studio’s general manager, partner and minority equity owner.

Auerbach, who launched his new band, the Arcs, in Studio A in June, says, “Since Lee’s been here, it’s started to form into something more like what the founders had in mind.” Devendra Banhart (who feels such blood-brotherhood with Foster that he inked him with a tattoo at the studio) says, “Lee was the person who single-handedly reanimated Electric Lady.” To Ronson, most of whose hit 2015 album, Uptown Special, was mixed at the studio, Foster “made it somewhere that musicians and creative people and singers want to be. He feels like one of us.”

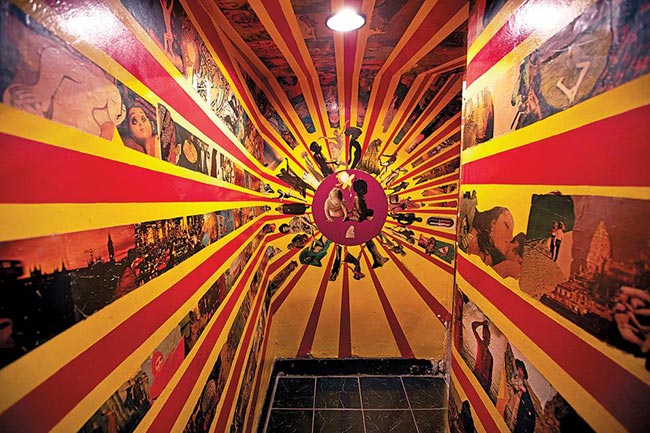

The decoupage mural that decorates a bathroom was created by then night manager Daniel Blumenau in 1970. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIO SORRENTI FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

The decoupage mural that decorates a bathroom was created by then night manager Daniel Blumenau in 1970. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIO SORRENTI FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

SO HOW DID A KID from Tennessee end up with the keys to Jimi Hendrix’s spaceship? Sitting in his upstairs office, (a Fender Telecaster signed by Keith Richards —“To Lee, One Love, KR”—leans against a wall), Foster, 38, reminisces about his upbringing in Smithville, on a farm 60 miles from Nashville. His father was a wildlife supervisor and his mother was a schoolteacher. The first song he remembers hearing is “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys,” playing on an alarm clock in his parents’ bedroom, when he was 4. Growing up he never considered a career in music. “We were told, ‘Boys pick up a rake; girls can do that froufrou stuff.’ ” The summer that Foster was 9, a neighbor, the country singer John Anderson, brought Elton John’s longtime lyricist, Bernie Taupin, to the Fosters’ house for a supper of crowder peas and frog legs. A snapshot shows Taupin standing in the living room, his arm on the boy’s shoulder. Young Lee looks downward, smiling and shy. He didn’t know that, while he was chasing hens and riding mules, AC/DC was mixing Back in Black at the music studio 800 miles away that would become his home. Like him, AC/DC had to buck the doubters: “I’m just not hearing any hits on this album,” a record exec told the group, according to Electric Lady lore. It became one of the top-10 best-selling albums of all time.

At 18, Foster enrolled at Middle Tennessee State University to study to be a rural vet. Unmotivated and frustrated, he coasted and flailed until he met a blond blues singer on the quad. “She was my Penny Lane,” Foster says, referring to the character in the movie Almost Famous who introduces a wide-eyed novice to the rock ’n’ roll scene. He hadn’t realized MTSU had a music school until she walked him across campus and showed him. “It was like the world opened up,” he remembers. Switching majors, he discovered Jimi Hendrix, got a white-strap guitar and, in his senior year, landed a three-month unpaid internship at Electric Lady, selling a baby-blue Mustang he’d fixed up to pay his way. When he got to the studio, expecting a hub of creativity, he found a place in the doldrums. Not only was it “depressing,” but “it hurt me to see such a monument being run the way it was.” Demoralized, he went home to Tennessee after the internship ended. He had a standing offer to return to Electric Lady, but “given the state of things” was reluctant to accept it.

By the fall of 2002, when he couldn’t find work in Nashville’s music industry, he started to fester and float. Soon an old Smithville friend, Tim Pack, intervened. Driving to the house where Foster was staying, Pack told him to get in the pickup and took him to his home on nearby Short Mountain. For the next nine months, the men worked from dawn to dusk, landscaping, mowing and painting houses, and tending 90 calves Pack had bought to raise and sell in the spring. “His point was to show me what I would be doing for the rest of my life if I stopped now,” Foster says, choking up.

At night he and Pack would meet on the porch, smoke and talk, and Foster would fret about whether to return to Electric Lady. As the weather grew cold and wet, the calves got pneumonia. “They were dying, and we’d bury them; their little hooves were stickin’ out of the mud. It was just really dark,” Foster says. One night, Pack snapped when Foster again began his agonizing and “I hate to say it, just kinda whining,” as Pack puts it. Bouncing himself back and forth across the door frame in imitation of Foster’s indecision, “he said, ‘Watch this,’ and he walks out into the dark,” Foster recalls. Three days later Pack drove Foster to the Atlanta train station. “Before he let me out of the car, Tim says, ‘Tell me three things you’re gonna accomplish in New York.’ ” Foster thought and answered, “ ‘I’m gonna take over the management of Electric Lady, I’m gonna make a record with Ryan Adams and I’m gonna smoke a cigarette with Keith Richards.’ I hugged him, got on the train and, 24 hours on, here I was again—ready for act two.”

Studio A, designed by John Storyk. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIO SORRENTI FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

Studio A, designed by John Storyk. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIO SORRENTI FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

FOSTER HEADED straight for Electric Lady with his suitcases. The gates were locked. A technician showed up at 9 a.m. and, seeing him camped out on the sidewalk, hollered, “Electric Lady and the tramp!” Once Foster made it inside the doors, he was surprised by what he found. After the soulquarians had departed, the place had gone further downhill. “Electric Lady was like a sick human being,” he says. “It was pale gray and gaunt and tired.” His voice rises with indignation as he recalls, “Someone had taken a Jimi Hendrix calendar, cut out the photos and put them up in cheap plastic frames.” He pauses. “To me it felt like the building was being neglected.” Three weeks later, the technician quit, on a morning when a local radio station had booked Radiohead into Studio A to perform two concerts, the second of which would be relayed live. After the first performance, the ISDN line went down; there was no way to transmit the second show. Refusing to give up, Foster had a board mix put together of the first performance and cabbed it to the radio station. The show aired as scheduled. The next day, Foster was made operations manager. He was 26, alone in New York, and had nobody to turn to for advice.

Reverting to what he knew—carpentry, painting and plumbing, Foster began to overhaul the building. Working around the clock, he slept in the studio, using piano covers for blankets. At 7:30 a.m., he would wake up, walk around the neighborhood and return when it was time to open the doors. Kaplan took notice. “You could see he looked at [the studio as] if it was a temple,” says Kaplan. “You couldn’t kick him out.” Less than two years later, Kaplan made Foster studio manager and gave him a year to get the studio back on its feet. “ ‘Make it work or we’re gonna have to shut the doors,’ he told me,” says Foster.

After he fixed up the place, Foster still could not lure musicians in to record. He started going to downtown clubs where the Strokes, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Ryan Adams were playing, talking up the new, improved Lady and getting to know the crews. For months, every time he saw Adams’s guitar tech, he begged him to tell the rocker he would get a free day at the studio. No response.

And then, one morning in 2006, at 5 a.m, Foster woke to a phone call. It was Adams. “Hey, you remember you said you’d give me that free session?” Adams asked. “I’m here now.” (“We were probably good and tanked,” Adams says now. “The bars close around then.”) Foster rushed to Electric Lady and let him in. That day Adams recorded the song “Two.” He was impressed by the vintage analog equipment Foster had installed in the control room—previously, Adams had recorded at “this little awful studio” on 14th Street that was digital-only, “not my thing.”

Over the next nine months, Adams cut the album Easy Tiger, and he and Foster became buddies. “Lee is family to me,” Adams says. After word of Adams’s stay got out, Patti Smith booked in to record her 2007 album, Twelve, and found she liked the revitalized studio. “Lee is constantly taking care of things technologically and making sure people are happy,” she says. The industry took notice. “All of a sudden,” Foster says, “Bowie’s back, Elvis Costello is here, Clapton’s here.” Around that time, Hollywood came calling: A scout needed a location for the movie Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist. The director and producer were so enthralled by their tour that they wrote Electric Lady into the script. The music industry was still floundering; and yet, says Andrew Miano, a producer of the film, Foster “placed the studio back in the discussion of where to record, mix or make your album.” Soon, a new generation of performers arrived, including M.I.A., Kanye West and Haim.

In 2010, Foster decided he wanted to take over the studio himself. Kaplan gave him his blessing to find a new owner, and Storyk introduced Foster to a music-loving private-equity-fund manager named Keith Stoltz, who respected the Hendrix legacy and had a passion for vinyl records. After the two met, Stoltz bought the business—on condition that Foster continue to run it. Together they expanded the studio space and staff and formed Electric Lady Artist Management in 2012. Foster and his Nashville associate Kirby Lee now represent four emerging groups—Nikki Lane, Hurray for the Riff Raff, Clear Plastic Masks and Mechanical River. That same year, Electric Lady co-founded an annual festival at Willie Nelson’s Texas ranch called Heartbreaker Banquet. This spring,Mick Jagger dropped by, after HBO greenlit a series he and Martin Scorsese had sold, about a young music executive in the ’70s. Afterward, HBO booked Studio A for three months. And this August, Foster launches the concert series “Live at Electric Lady” and announces the Electric Lady Records label, which will release 12-inch LPs of the performances, as well as seven-inch records under the heading “Generation Club.” Foster says, “I want to show people we’re not just a studio.”

To mark Electric Lady’s 45th anniversary, Patti Smith inaugurates the live series, performing her entire first album, Horses, in Studio A, where she recorded the original in 1975. The concert will be pressed onto the debut Electric Lady Studios LP. This was her idea. “It occurred to me that it might be nice to perform it there, as a gift to Lee,” she says. In “all the configurations I’ve played there,” she says, “having Lee has been the best experience for us all. He has made me feel like it’s a home.”

One day not so long ago, Bernie Taupin booked time at Electric Lady to work on a new Elton John album. He had long forgotten the little kid he’d met in Tennessee, but the kid remembered him. Calling his dad, Foster asked him to mail the Smithville snapshot to New York. When Taupin arrived, Foster walked into the control room and handed him the photo. “He looks at it, looks at me, and says, ‘Why do you have this? I haven’t seen that in 20 years.’ ” Foster smiled. “I said, ‘That is me you’re hugging.’ All this has come full circle.”

1 – The vintage analog Neve recording console Foster installed is a draw for musicians who prefer a less slick, warmer sound. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIO SORRENTI FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

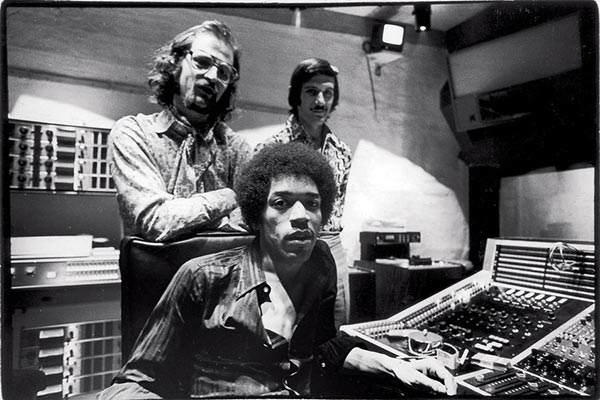

2 – Jimi Hendrix with engineer Eddie Kramer (left) and studio manager Jim Marron in 1970. GETTY IMAGES