Last October, Foo Fighters belted out the lyrics of their latest single, “Sky Is a Neighborhood,” to a sellout crowd of 6,000 at the opening night of Washington, D.C.’s newest music venue, The Anthem: “Gotta get to sleep somehow/Bangin’ on the ceiling/Keep it down!” But nobody in the adjacent apartment towers was doing any bangin’. They couldn’t hear a peep.

While those inside heard rich, clean, loud rock ’n’ roll.

Anthem owner Seth Hurwitz and developer Monty Hoffman of PN Hoffman, which built the $2.5 billion entertainment/residential/hotel/restaurant complex on D.C.’s Southwest Waterfront, set out to provide a top-tier music venue with great audio. They also wanted to be a good neighbor.

Hurwitz, whose I.M.P. owns the city’s Pollstar Award-winning 9:30 Club and runs the historic Merriweather Post Pavilion in nearby Columbia, Md., was looking to build a place with a capacity somewhere between the 1,200 of the 9:30 and the 18,000 of Merriweather. Besides those venues, he notes, “We were always renting venues, for decades, that were not built for music. Traditionally, promoters rent venues that were built for sports or civic or multi-use reasons. And audiences have just accepted this as a standard—these square peg in a round hole places.”

The opening night marquee for the Foo Fighters. The commercial/residential density of The Wharf led to sound isolation challenges Photo by John Shore

C. Russell Todd of Akustiks, Hoffman’s sound isolation consultant, knew from the beginning that Hurwitz wanted the intimacy of the 9:30 Club, but he wanted more people inside: “Seth said, ‘I just want to do this, but bigger.’ And then Monty added, ‘Yeah, and I want to put apartments right next to it.’ Everybody knew, ‘Okay, we’ve got our work cut out for us!’”

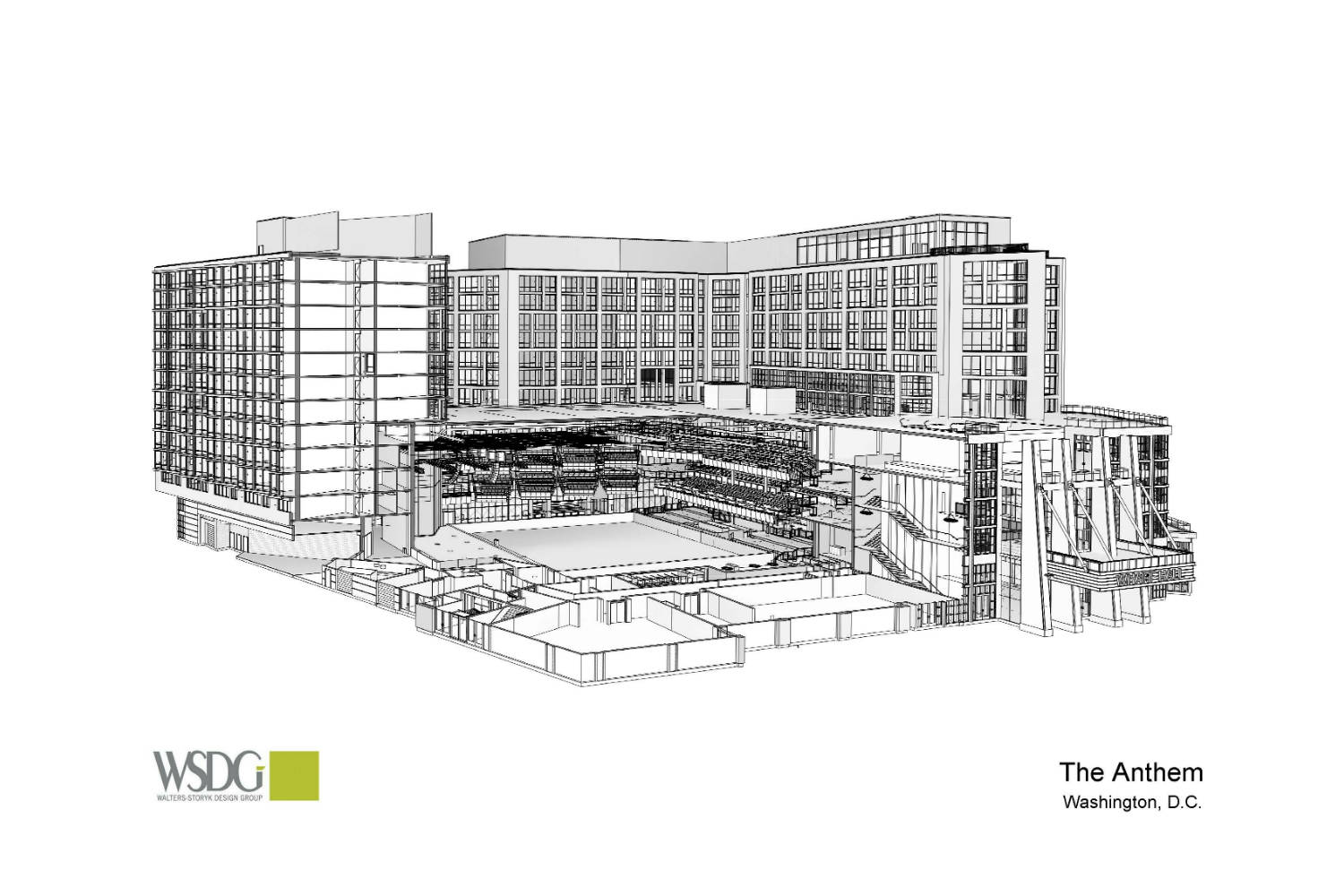

The overall design for The Wharf was handled for Hoffman by architect-planners Perkins Eastman, who designed the overall structure. The Anthem’s specific interior architectural design was by renowned designer David Rockwell and the Rockwell Group. While Akustiks worked on the developer side, Hurwitz brought in Walters-Storyk Design Group (project manager Josh Morris), with whom he’d worked previously on 9:30 and elsewhere, for peer review of acoustic, isolation and sound design.

On the isolation front, the design approach was one Akustiks had taken previously in concert hall design—though, in this case, in reverse. “We’re making a lot of sound and vibration inside the hall; here, we need to make sure it’s quiet on the outside,” says Todd, adding that the design called for a hybrid box-in-a-box: “A building within a building, but hybrid, in that there’s a complete acoustic joint all the way around the room. It’s a concrete box that’s decoupled from the rest of the structure at the perimeter, with acoustic isolation joints.”

Structurally, The Anthem’s isolation starts with isolation slabs for the floor and the roof. The floor’s design consists of what’s known as a jack-up isolation slab—a 6-inch concrete slab supported on the structure’s 12-inch slab by a network of isolator devices, manufactured by Mason Industries, often used to isolate vibration of mechanical systems in buildings. “The floor slab sits on vibration isolation, so the bass energy, the crowd movement, doesn’t get into the structure and get transmitted up into the apartment towers or adjacent structure,” Todd explains.

From left, I.M.P. technical director Chris Robb, with chairman Seth Hurwitz, in front of The Anthem’s DiGiCo SD12 FOH console Photo by John Shore

The two-piece neoprene isolators (a base, plus an inverted bell-shaped dome, connected via a screw device) were placed by general contractor Clark Construction at 4-foot centers around the entire 133×135-foot Anthem floor. Plastic sheeting is placed upon them, with the floor slabs’ rebar on top, bearing onto the dome pieces of the isolators, after which the slab concrete is poured. After the concrete is cured, a crew slowly raised the floor slab, using large T-wrenches penetrating the openings of the tops of the dome pieces on the slab’s surface, methodically turning the screws that separate the two pieces of the isolators, eventually raising the entire floor slab enough to leave a 2-inch isolation air gap between the two slabs. Any vibration from either music or audience is transmitted, from the domes, via the screws, to the neoprene bases of the isolators and fully attenuated.

Walls are constructed of 6-inch concrete block, bearing on the floor slab—with a 2-inch gap between them and the building’s 12-inch concrete walls. Wall penetrations for ductwork, piping, conduit, etc., Todd notes, have to be resilient, using flex connections and vibration isolation hangers. “This is where we’re totally dependent on the contractor’s due diligence to pay attention to every detail, or else it would fail.”

The roof, like the floor, is made of a floating slab, one upon the other, with vibration isolation. “The roof would otherwise act as an ‘area source,’” Todd explains, which, unlike a point source, does not decay in audio level with distance. “That means that any noise being transmitted would be just as loud at the roof level as it would for a resident 20 floors up. And you hear nothing when standing on that roof garden.”

Handling Reflections

The approach for handling sound reflection was twofold: eliminating low-frequency reflections and allowing some mid- and high-frequencies to be reflected to give the room life. With EDM acts making regular visits to the Anthem, low frequencies could have been a problem.

The size of the empty club gives an idea of just how massive the isolation challenge was with the box-within-a-box construction. Photo by Dave Barnhouser/13th Hour Photography

“That’s the big room acoustic challenge in this space,” Todd says. “In an arena, if you don’t deal with the bass energy, the room begins to sound muddy; there’s a lack of clarity of the bass. By absorbing the bass energy, not only does the mix engineer not have to fight a lot of extra low-frequency energy in the room, it also decreases the amount of sound that’s trying to bleed through to the apartments.”

The main method for handling low frequencies in The Anthem is via lapendary panels, made by MBI—4-inch acoustic panel material draped two feet from the ceiling surface, to allow low frequency energy to be trapped and absorbed. “We place it a quarter-wavelength away from the reflective surface, where the particle velocity is the highest for the incident wave,” Todd explains. “You could either do that or put two- or three-feet-thick material up there, which is quite costly.”

Some reflections were allowed, mainly off of the “tray”-type balconies—cantilevered seating platforms that project out into the room. “We want to have some life in the room, especially with respect to the crowd clapping, etc.,” Todd says. “I hate a dead room.”

“From an acoustic standpoint,” says I.M.P. technical director Chris Robb, “once the people arrive, you have, in a sense, ‘water bags,’ as I often describe rooms to engineers. A lot of acoustic absorption happens between soundcheck and the show. So besides the absorption taking place on the back walls, the sloped seating from the balconies help absorb some of the energy naturally, just due to the presence of the audience.”

Make It Rock

The audio system at The Anthem is robust, and quite purposefully so, says Robb: “Not many venues of this size will offer full production. We provide the current, best production we can, in hope that acts won’t want to bring theirs in. We’re hoping we have more and better than what they’re carrying. Labor’s expensive, and nobody wants an 18-hour day.”

The sellout Anthem crowd roars for Phoenix, with d&b J-Series P.A. Photo by Victoria Ford/Sneakshot

The Anthem has two DiGiCo SD12 consoles—one at front of house and the other at the monitor position. FOH is in a more-than-ample raised space, twice as big as most technical riders call for, Robb notes, with a guest position available to its left, with room still to spare. (Interestingly, when Foos mixer Bryan Worthen was on site, he set up on the floor, instead of the raised mix position, to allow him to be out of direct sound path of the band’s rather loud guitar amps. “If you already have a ton of guitar coming at you,” Robb notes, “you’ll tend to compensate and lower it in the mix; but then you go to the upper balcony, and you can’t hear guitars.”)

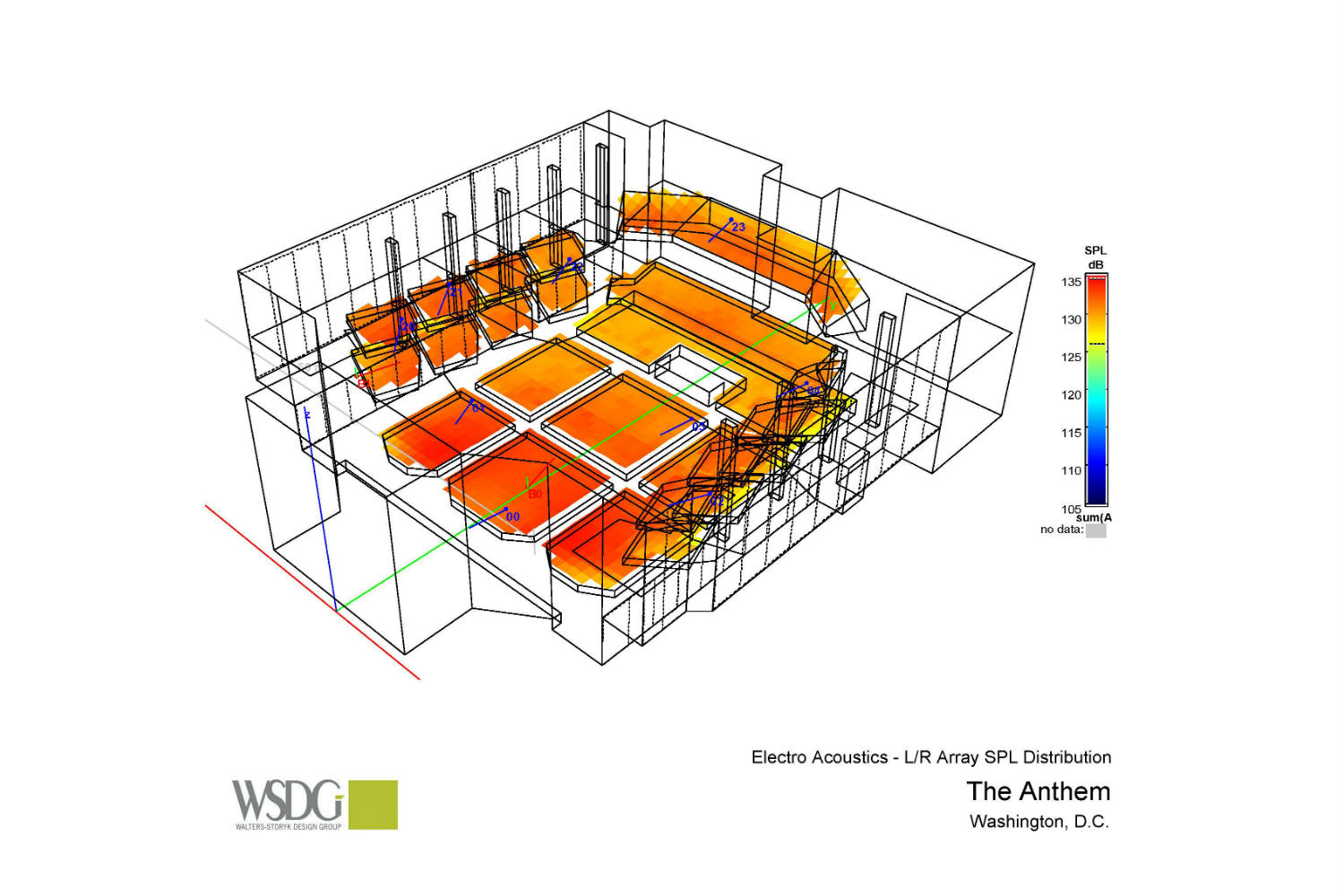

For speaker arrays, Robb went with the I.M.P. company standard, the d&b Audiotechnik J-Series, as he had installed at the 9:30 and elsewhere around the I.M.P. world, provided by vendor Eighth Day Sound (with help from the company’s install specialist, Tom George, and head of Global Sales Owen Orzack). The dual speaker arrays, suspended from movable trolleys (built to follow the moving stage, for instances where it is placed closer to the center of the room), consist of six J-8 boxes per side, with 80 degree throw to the farthest reaches, atop eight J-12s, with 120 degrees to widen out to spread the sound for patrons on the floor. The former are most important, Robb notes. “It’s easy to make it sound good right in the middle of the room on the floor, and very complicated to make it sound as good in the very last row at the very top of the balcony seats. So that’s where I start, and then I work my way back to the floor.”

Six d&b J-Sub subwoofers are hung behind each of the main arrays, with four more Infra-Subs placed under the stage. “The 30 to 40 Hz is where everybody pushes, to get that chest thump, visceral impact,” Robb says, noting that the whole system is driven by d&b D80 power amps. “They’re sort of a black-box, proprietary d&b amp, with four channels per rack unit. And it’s all controlled via network from the mix position, so you can have full control to all the functionality on the amps from the mix position.”

In designing the venue audio array system, WSDG used several modeling software platforms to optimize an exact system. Finalizing the solution, Robb utilized d&b’s proprietary ArrayCalc modeling software.

Jack-up isolators and reinforcement bar set in place, awaiting concrete for the Anthem floor. Photo courtesy Akustiks

WSDG principal John Storyk notes that most major speaker manufacturers have array-calculating software, “But these modeling tools are essentially for coverage only; they rarely if ever take the room into account, as if the system environment had no boundaries. That’s clearly not the case with The Anthem.” In this case, WSDG used CATT-Acoustics as the primary modeling software, along with two proprietary engendering tools. “We work well with Chris,” Storyk says. “Working with the 9:30 Club team has always been an honor. They’re super-capable, but they also want to listen to our thoughts and ideas.”

Some fine-tuning was done with help from LCD Soundsystem’s system tech Richie Gibson, who, Robb notes, is with 3tinybones and, on occasion, is used for touring support by Eighth Day Sound. “EDS has a big list of great engineers they call on, and Richie sometimes works for them freelance. His suggestions and recommendations were really helpful in the fine-tuning phase after the install, it was much appreciated! The Array Processing is a great feature. We are always playing with it and improving an already great system, and it really lets you dial in exactly what the visiting engineer is looking for or what the style of performance really needs.”

The resultant combination of a well-crafted acoustic design, solid sound isolation, and a finely tuned audio system means, as is often noted of The Anthem, “There’s no bad seat in the house,” even with three levels and a 57,000 square foot base.

“For an audience, all they want to know is it sounds good,” says Hurwitz. “It’s like a restaurant—it doesn’t matter how the food got to the plate, it’s gotta taste good. They need to hear the music and it has to sound good. You can’t explain to someone who’s standing in the wrong spot, ‘Hey, if you move over there, it’s gonna sound better.’ It has to sound great everywhere.”

WSDG-Walters-Storyk Design Group • wsdg.com/projects-items/the-anthem