Walk on the Ocean: Composer Carter Burwell Crafts a Stunning Studio

By David Weiss

Inspiration doesn’t exactly strike Carter Burwell. Rather, he soaks it in.

The composer’s distinctive voice has been essential to over 100 productions, in an enviably long career that has made him the top choice for many of film’s most inventive directors. Burwell’s is a long list of credits that counts Todd Haynes’ Carol, Martin McDonagh’s Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, Being John Malkovich from Spike Jonze, plus every Coen Brothers movie save one including Fargo, The Big Lebowski, O Brother Where Art Thou, and No Country for Old Men. Most recently, his assignments have included Apple TV+’s new release The Morning Show, the Bill Condon-directed The Good Liar, and the Golden Globe-nominated stop-motion animation Missing Link.

Burwell’s outstanding orchestrations—especially ideal for subject matter that plugs into the darkly ironic side of mankind’s psyche—have long been connected with his East Coast citizenship. A prolific powerhouse, Burwell helps maintain NYC’s elite film scoring credibility to a world where when LA composers are still king.

Only he isn’t actually in NYC anymore. In this extremely insightful interview from 2011, SonicScoop found Burwell cranking out classics from his WSDG-designed The Body studio in NYC’s chic TriBeCa neighborhood, even after he’d moved his family to Amagansett in Eastern Long Island. But now he’s all the way gone, living and working out of a rebirth of The Body in his home on a bluff looking out over the Atlantic Ocean near Montauk Point.

A 600 square-foot sonic space attached to the second floor of Burwell’s ultramodern habitat, the new The Body was once again designed by WSDG, guided by the firm’s Founding Partner John Storyk and Partner/COO/Project Manager Joshua Morris. The result is nothing less than a creative oasis, one that allows Burwell to dive deeper than ever into every single thing he holds dear.

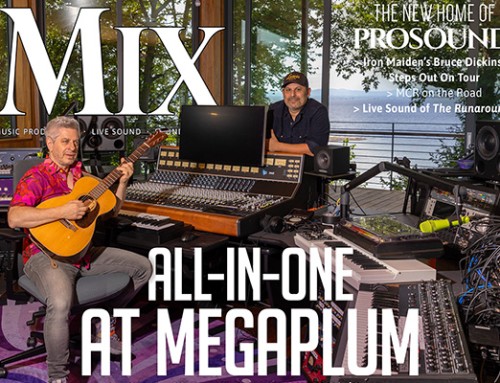

Carter Burwell in balance at The Body, his new studio on Eastern Long Island. (Photo credit: Tycho Burwell)

Here’s my first question for you Carter. It had been about 20 years since you built your studio in Tribeca. Before we get into how technology and creative tools have changed, how have you changed as a composer in that time?

Well, it’s a fair question, but the reason I say that is because I don’t feel like I’ve changed that much. I have more experience, and I guess one of the changes in that time is that now I’m much more comfortable and much more often orchestrating and conducting orchestra, which is something I wasn’t (doing previously).

I came from a rock and roll background, so if you go back 20 years, it’d be right around when I was deciding that I was going to start orchestrating and conducting my own music, which was a big leap for me.

Pursuant to what you just said, Carter, perhaps speaking immodestly, why do productions hire Carter Burwell today? What are they looking for from you? What do you deliver to them that maybe no other composer does or can?

Well, hopefully every composer has their own voice. I think that people do come to me largely to hire my attitude towards film, the angle I take on the storytelling.

Also, for instance, I like melodies and there’s a lot of film music that isn’t melodically driven these days. Of course I’m not in a perfect position to answer your question because I never hire me! It’s the other people who do.

But I think that especially if the film involves a dark, ironic worldview, then I fit that naturally. That is my worldview, I write that way and that’s why I get along with certain writer/directors like the Coen Brothers or Martin McDonagh or Charlie Kaufman.

You’re touching on something that can get overlooked, which is that the personal relationships that you develop with the writers and directors are important. That really matters, right?

Yeah, it is true. It just makes that process easier if you actually trust each other. It means that you can be more creative because you take more chances: I’m not worried that I’m going to send Joel and Ethan Coen something they didn’t expect and they’re going to fire me the next day.

That can happen. In situations where the director’s got a hundred things [they] have to think about. They hear this music from somebody they haven’t worked with before, they don’t understand the music and they say, “That’s it. I’m going to hire somebody else.”

I should also point out, because I live at the end of Long Island, basically as far from the industry as you can be without being in the ocean, it’s hard for people to hire me. The directors know that they’re not going to be able to drop by my studio every day. I totally understand that, that counts me out for a lot of projects in Hollywood. So I like to think that if someone takes the trouble to hire me—because it is a little bit of trouble—they want me. They’re not hiring me so that I can do a copy of John Williams or something like that.

Moving to Montauk

The last time I visited you was a studio in downtown NYC’s TriBeCa neighborhood. Did you move to the Montauk area full time, and what was your impetus for building the new The Body studio there?

An acoustically accurate ocean view. (Photo credit: Tycho Burwell)

I did move here full time. Almost from the time I moved here, I began the process of trying to have a studio, because I work at home and I need a soundproof space that’s also acoustically accurate. So I can actually judge what I’m listening to, and when I send it to someone in California or London or wherever they’re going to hear the same thing that I’m hearing.

But because of where I live, I had to get approvals from FEMA and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and of course the local town. And it actually took about seven years to get those approvals. But I began working on it as soon as I moved out here.

And so I take it you were finding a way to work out there without a full-blown studio?

I was literally working in a pantry off the kitchen for those seven years.

Montauk is a beautiful place to visit. I know it kind of goes without saying, but what personally attracted you to the area and why is it so right for you as a person and creatively?

What I was looking for was to get out of the city and into a more natural environment, not something where you just see the same three or four species all day long.

And so I looked at a lot of different places. I like Northern California too, for instance. But I think what this area had was that nature: A lot of the land is protected and will never be developed. But it’s close enough to New York that my wife and I could still stay in touch with our friends there. Her family is on the East Coast, mine is as well. So it has some beauty and serenity, but we’re not completely away from New York City.

Building The Body

Carter, what were the new opportunities that you want to realize with the new version of The Body? Aesthetically, creatively, and technically, what were your visions?

This is going to lead to a question you hinted at before, which is how much technology has changed. When I built my studio in the city 20 years ago, I still was working with all these hardware synths and there was a huge amount of hardware involved in what I do. Now it’s almost all software.

That meant that I could build a studio that was much more slimmed down that didn’t have to have all these rack spaces. In the end, the brief we gave John Storyk was, “Can we replace all of that equipment space with windows?” so I take in the beauty of the place that I live. That was really one of the most important things here: to try to get the footprint of the hardware as small as possible and then open the space up for what’s outside.

Also in the 20 years since I built the New York room, there’ve been all these new acoustical materials developed. That has allowed us to tweak things in a way that we couldn’t before so that, even though it’s still a small room, it’s handling a lot of those frequencies better.

Can you give me an example of that?

One of the main ones is that, as I said, I wanted lots of glass. I wanted to be able to see the outside, but glass is not an acoustically friendly material and most studio designers try to make sure it’s not anywhere near where your speakers are pointed. We’ve used this diffractal that’s made out of clear Lucite that goes in front of my window, that is doing the same thing that a wooden reflector would do to break up the reflection. But I still have all the light and I can still see out my window.

What are you using for monitors now, and did you perhaps get the chance to improve your sweet spot in a surround situation?

Mostly the sweet spot improvements came from the use of materials to make sure that the sound got diffused in an accurate way in the room. For the monitoring, I’m still using Genelecs. I got slightly smaller ones than I had in the city, which I realized were overpowered for what I do. I’m not a hip hop producer, I didn’t need the big speakers.

These Genelec 8350A’s are great because they’re not large, they give me a very accurate sound but they don’t get in the way of the space. It’s not like I walk into the room and I immediately think, you know, “Speakers!” the way some studios are. So I really like that.

Since a great deal of your synths have gone in the box, I’m sure everyone is interested to know what you’re using for strings.

Most of my scores do end up getting performed and recorded by live players—I mean, essentially all of them. But the strings I use [for composing], most of the orchestral samples I use are from the Vienna Symphonic Library. And I also use some Spitfire ones particularly for more specialized uses, and Omnisphere. And for processing I really love the Waves packages, they are all great.

Know Your Architect

You said there was no “Getting to know you dance” with John Storyk and WSDG, since this was the second studio you had collaborated on. How would you characterize the benefits that the ongoing relationship with a studio designer like John brings when you’re doing a build like this?

A WSDG blueprint for The Body.

It really did save a month or two and who knows how many conversations, because one of the battles we had back in the city was that I wanted all these windows, and he was really loath to put them in because it was going to have a negative impact on the sound.

And so we were able to begin this discussion from the assumption that, regarding windows, we’re going to find a way to do it that works. He knows that I’m very visual. I had a personal need for a visually peaceful space—I don’t want to be distracted by colored lights, or really anything. He knew that that was also part of the package with me. So there’s a lot of discussions we didn’t have to have, because he already knew me and I knew him.

I also interfaced with (WSDG Partner/COO/Project Manager) Joshua Morris a lot on the build. His presence onsite was very important because the contractors I have out here are not used to building something like this. A lot of times we would get to a point and construction would just kind of cease because they didn’t know what to do with these specialized materials and special instructions for how to handle them. Then Josh would come out, or we’d get him on the phone and get an answer very quickly.

A Creative Oasis

Carter, I know you had a plan and a vision for this room. It sounds like it was really fulfilled for you. However, I’m curious if once you got it broken in, what are some of the pleasant surprises that you’ve experienced with the new space—how is it perhaps exceeding what you thought it could do for you creatively?

Carter Burwell at the helm. (Photo credit: Tycho Burwell)

I’ll say that at the simplest level when I walk into this room in the morning, about to sit down to work, my immediate reaction of walking into the room is pleasant. I exhale and I feel calm. And my business is not necessarily a calm business, the deadlines are very brutal. Frankly a lot of the time, it is very stressful. So to know that, when I come into my workspace, I’m not immediately faced with stress, but the opposite, that’s a great thing. It makes me want to come into the room. It’s nice.

Speaking of the business, how have you observed that music for picture is evolving? Where do you see it headed in the business sense, and creatively?

Well I think that putting aside changes in taste or fashion, you can’t talk about it right now without talking about the streaming services and the sheer amount of content that they’re trying to create. I’m working on a show for a streaming service right now and the executive I work with is making more than a hundred other shows at the same time. That’s unheard of.

Believe me, there was nothing like that when I started out. The biggest studios were never making more than a few things at once. There would be years of development, right? Today’s streaming projects, they develop them in a few months, shoot them, and then they’re live on the platform a month later because they don’t have to advertise or market them. That’s just a very different model.

The good part is there’s so much work right now, which is good for young composers. So that whole question of how do you get your foot in the door? How to get started? When I was working on feature films, that was a very hard question to answer, but right now there’s so much being made that they just desperately need composers for all these shows. So that’s a good thing.

I don’t know what it adds up to creatively though, because I think that a lot of these shows are really being rushed, and they’re putting a lot of money into them so they look and sound fabulous, but they’re not putting a lot of time and thought into them. And I think that’s unfortunate, but that’s just the way it is right now. It’s just a gold rush and everyone is trying to stake a claim.

Here’s my last question: People are going to going to look at this article, see the pictures of that studio, and say, “Carter Burwell is living the dream.” Is that accurate?

I think that is pretty accurate. I mean, without question: It’s a great luxury to be able to live here, work, and have this beautiful studio in my house with my family.