The Mind and Music of Carter Burwell

By Tom Kenny

Photos by Tycho Burwell

A few years back, at age 40 and well into a highly successful career as a music composer across all forms of media and art, Carter Burwell enrolled at NYU to take master’s level courses in the biology department, He wasn’t considering a career change; he was simply interested in learning more about viruses and how they behave.

That may seem unusual on the surface, and it would be for most people, but it’s not when you consider that Science and Art—in all their many and varied forms— have been parallel and consistent tracks throughout Burwell’s life.

He’s been a cartoonist at the Harvard Lampoon, an early computer animator, a computer musician after auditing coursework at MIT in the 1970s, a vocal performer with The Harmonic Choir, specializing in overtones, a director of technology at the New York Institute of Technology, and he has maintained a lifelong interest in biology, neuroscience, architecture and human perception, among many other pursuits. He still doesn’t consider music his career.

“I knew a lot of musicians at the time where music was their only interest, career-wise,” Burwell says. “And they might grab a day job to make ends meet. That’s not true for myself. I’ve always had a lot of different interests and I never expected music to be a career. Music was more of an avocation, something I did for pleasure and therapeutically. I never expected to have a career as a musician. I just always wanted a good random mix to whatever was interesting to me. I wasn’t raised with the concept of, ‘You should have a career.’ That’s not something my parents ever imprinted on me. And so I never have.

“But I do think that as a matter of course, artists should be exposed to and investigate lots of different modes of expression,” he continues. “Even if you are ‘just a composer’ or ‘just a sculptor,’ I still think that there’s a lot that you can get out of, say, the literature of architecture. But of course, once you have a career in some field, I think circumstances conspire to force you to spend most of your time and effort in that one area, and you have to make more of an effort to try to see what’s going on in other fields.”

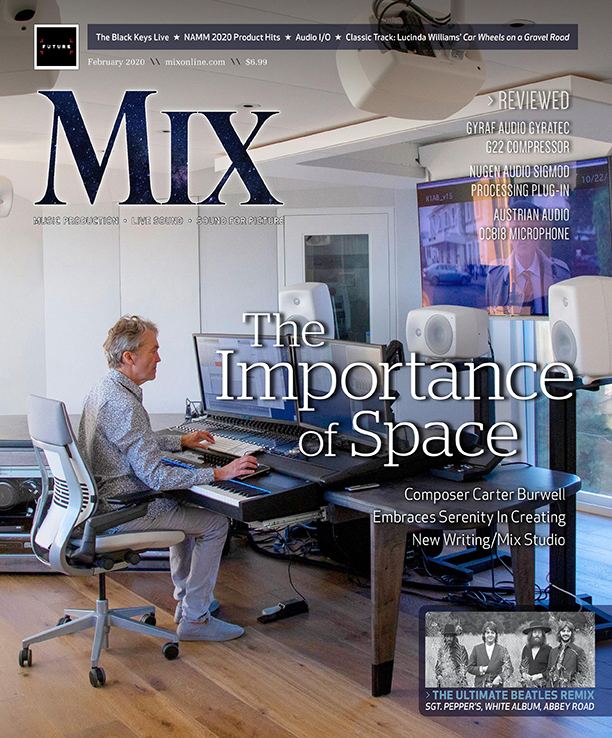

Carter Burwell in his WSDG-designed studio, located at the end of Long Island at Montauk Point, NY.

For someone who doesn’t really consider music a career, Burwell has nonetheless been quite successful at it, with a filmography that is as wide and varied as Barton Fink, Raising Arizona, Being John Malkovich, Three Kings, The Blind Side, Fargo, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Conspiracy Theory, Adaptation, No Country for Old Men and countless others. He has been nominated twice for Oscars, for Todd Hynes’ Carol in 2015 and Martin McDonagh’s Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri in 2017. He has done all of the Coen Brothers movies, save O, Brother, Where Art Thou? and Inside Llewyn Davis. In 2009 he received the ASCAP Henry Mancini Award. Not a bad resume.

The only formal music training Burwell received was piano lessons as a ten-year-old, followed by drum lessons. Neither really interested him, though he does give them credit for teaching him to read music. It was at Harvard in the early to mid-1970s that he found some kindred souls, some misfits and outcasts, the types of people he’s always been attracted to. Music was a side project to his bachelor of science degree. He says that “he played for himself through college,” and in his senior year found a group of friends who were also interested in bands, and in what was happening in punk rock at the time. At the end of the year, they decided to go back to New York, his hometown, and be a band.

And that’s where the interview begins.

MIX: New York City must have been quite an exciting place to be when you came back home.

BURWELL: Oh, yeah. That was 1977, ’78, and it was it was a very exciting time musically. There’s no question. In my mind, it was a decision to go to New York or go to London. Those are the two places where the music I was interested in was happening, but New York did have a sort of special hybrid between the contemporary classical world, people like Philip Glass and Steve Reich, and the mom and pop music world. Those composers would appear on the stage in the same evening as talking heads or any number of punk bands.

New York’s the kind of city, unlike, say, Los Angeles, where you are really at street level with people all the time, literally rubbing elbows with people from around the world. And so it’s very easy to come into contact with musicians from Poland or China or India, you know. There’s a nice fluidity to it simply because of the nature of New York.

The centerpiece of Burwell’s studio is an Avid S6 32-fader console and a 7.1 Genelec monitoring system.

And then, just a few years later, while playing a gig at CBGB’s, the Coen Brothers walk in and at the end of the show ask if you would be interested in scoring a film they’d been working on called Blood Simple… True story?

Yes. True story. I didn’t know them at all. We’re the same age. And it turns out we have similar sorts of interests, and certainly similar sensibilities. I will say that as a general rule, when someone asks you to do something isn’t done before, it’s almost always a good idea to say yes. I mean, unless you think it’s actually going to kill you. Especially when you’re young, you have to say yes to things.

That first film, Blood Simple, was really just me playing piano and a bunch of tape loops and things like that. I didn’t have to put music on the page for anybody. So it was perfectly simple to do in terms of my knowledge of music. And Joel and Ethan kept saying, ‘Oh, this movie will probably never be released.’ So there wasn’t the same pressure you might have with an 80-piece orchestra sitting in a recording studio for a Marvel movie—not that I wouldn’t like that. But it was more like a soft introduction.

So you learned about spotting a film and things like that?

I don’t recall. I mean, I guess it must have happened that at some point we all sat at the KEM, which was the editing desk back then, and went through that film and spotted it.

But Joel was trained as a film editor. And I know that whatever we recorded, he then took it and moved it around. So whatever we spotted ended up, I think, largely being a moot point. They took whatever I wrote and they placed music over the frame. I put down something for three, four or five minutes, even though I don’t think anything in the film runs for that long. But I would do different renditions of things. I do remember having sitting with a stopwatch on the piano and playing something in thirty five seconds if they needed it.

There’s one fortuitous thing happened with regard to Blood Simple. I’m a film lover but I hadn’t really thought in any depth about scoring music to it. And I thought, ‘Well, I’ll, um, I picked up the TV Guide to see what movies were on. And Hitchcock’s The Birds was on. I watched it, and I recorded it so that I could then play it back to study the score. And at the end of each big dramatic scene, I would slap myself and say, ‘I forgot to listen to the music!’

Then after the whole film was over, I rewound it and watch again, and I soon realize that it doesn’t have a traditional score; it’s entirely scored with bird sounds. It was actually my first lesson in film scoring, and it was a very fortuitous choice of film. It showed me that a film could be really effective with a score that has nothing to do with violins and brass.

I don’t have a traditional compositional background, like a conservatory and composition training. I’m not that interested in some of the traditions of, you know, the voicing of Bach chorals and things like that. That’s just not my background. That’s not particularly interesting to me. But understanding how sound works and how it affects the mind is interesting.

I will never be able to recapture the innocence of Blood Simple, when we didn’t know how to synchronize the tracks, the picture and I didn’t know anything about orchestration. You know, that was a special moment.

And then Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing…

Certainly my one of my main criteria for choosing a project is that it not be something I’ve done before. But I’ve often been lucky in that, say, the directors that I work with, like the Coen brothers, they don’t tend to repeat themselves. After Blood Simple, they didn’t follow up with a film noir. They followed up with Raising Arizona. And most strikingly, the third film was Miller’s Crossing, for which they wanted an orchestral score. And they knew perfectly well that I had no idea how to do that. At that point, they could have hired Jerry Goldsmith. But they went ahead and asked me to do it, even though they knew I knew nothing about it. So that’s a kind of trust that I appreciate.

I knew before they shot a movie that they wanted me to do an orchestral score for it. So for months while they were shooting, I was reading scores of composers whose work I liked trying to figure out how and what they’re doing with the French horns, for instance, what they’re doing with the oboe. That was my approach to learning what an orchestra can do as an instrument. And yeah, I love it just because I came out smarter at the end of the project than at the beginning. I think the first thing I orchestrated and conducted was Fargo.

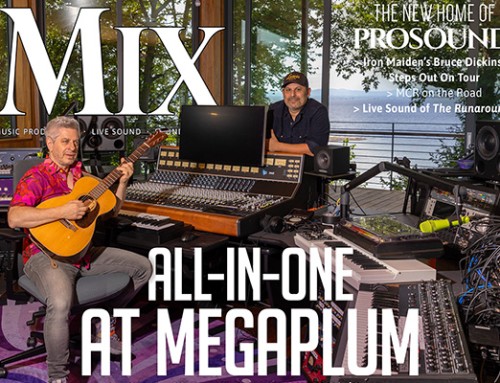

Carter Burwell with Mix editor Tom Kenny. Photo by Howard Sherman

Well, by 1992 you build your first pro studio, also designed by John Storyk, and it’s 5.1. You seem to learn pretty quickly. How did you learn recording?

Technology was in a way my way into music. I’m not a trained composer and honestly, not that much training as a musician, but I do have a good grasp of technology. And it allowed me to get into music that way through electronics and through digital technologies. I was very aware that using computers to do this was a new thing. I think the Synclavier came out right around the time I first did a score, and I worked with that a little bit. And we had a 16-bit A-to-D converter at New York Technology Institute. And so that’s why we’re writing code for sound editing at a time there were no commercial packages to do it.

Well, actually, it was in college my last year when I began to really have an interest in music. Harvard music training was very traditional and just not honestly not interesting to me, but they had an electronic music room sort of in the attic of the building and the professor that ran that was named Ivan Tcherepnin. He was not in that tradition. He had tape machines and he had parabolic mics that he’d stick out of the window to pick up voices down on the street level. And so he was coming at it from a very different perspective. More of my perspective.

Well, time is up, and I realize we’ve only touched on your entire career. But I do have to ask you about the amazing piano in your living room…

It was at Clinton Recording for years in New York, and before that it had been at CBS 30th Street Recording Studios. A New York Steinway from 1947. When recording scores in New York that became my favorite piano. I think it was Barton Fink, sort of a pianodriven score, where I played that piano and I just really fell in love with it. So whenever I had something piano-oriented I wanted to record. I would try to do it on that piano.

And then just when I was buying this house 10 years ago, I heard Clinton was closing, I immediately reached out to the owner. And I asked about the piano and he said he was looking for a museum that might want to buy it because of its history. I don’t know how many piano museums there are, but now I’m carrying on the next life of the piano.

Carter Burwell’s new writing/mix studio attached to his home on Montauk Point is an absolutely stunning piece of work—aesthetically, architecturally and acoustically. It sits on the second floor, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean from Burwell’s writing position, connected to the home via a walkway. The home itself, purchased 10 years ago and completely renovated by architect Maziar Behrooz, belongs in Architectural Digest.

This is actually the WSDG design team’s second project with Burwell, having designed a 5.1 room for his 10th-floor Tribeca loft back in 1999. The same demands were there for clean lines, pristine acoustics, and lots of natural light. Storyk was brought in early, as the plans for the house were being developed, and to give the a taste of how he would like the studio to sit, he took Storyk up iin a cherry-picker to show him the view.

Joshua Morris served as lead architect and project manager for WSDG. Systems integration was by WSDG Senior Systems Designer Federico Hugo Petrone. It also represents the final assignment designed by longtime WSDG resident HVAC genius Marcy Ramos, who sadly passed away soon after completing his work on the project.

The centerpiece of the studio is an Avid S6 32-fader console. The 7.1 monitoring system is all Genelec, with 8351A mains and 8300 surrounds. His composing keyboard is a Native Instruments S88. He writes in MOTU’s Digital Performer and notates in Sibelius. A 65-inch flat screen “flips down” from its motorized ceiling mount, and motorized sheer and blackout shades were installed to block sunlight for composing and mixing sessions.

The studio is a study in fully-floated isolation and is precisely tuned with RPG Acrylic Quadratic Residue Diffusors, and RPG Micro-Perforated wall treatments, as well as custom broadband absorption and diffusion –— all hidden from view behind fabric for a clean and ordered aesthetic.