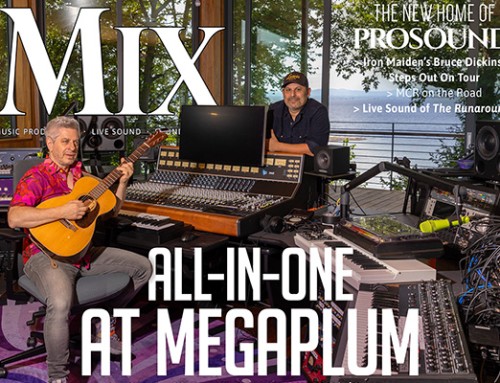

In the five decades since Jimi Hendrix founded Electric Lady, on West Eighth Street, the music studio has kept its look—and caliber—intact

A view of the wall inside Electric Lady Studios, in New York, Aug. 24, 2010. Founded by Jimi Hendrix in 1970, and still open today, it was an oddity for its time designed like a psychedelic lair, with curved walls, groovy multicolored lights and sci-fi erotica murals to aid the creative flow. (Michael Nagle/The New York Times)

A handful of recording studios have made it into the Zeitgeist over the years. Places synonymous with excellence, creativity, and often bad behavior—Abbey Road, in London; Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, in Sheffield, Alabama; and Stankonia Studios, in Atlanta, come to mind. But, for me, Electric Lady Studios, in New York City’s Greenwich Village, has always held the top spot.

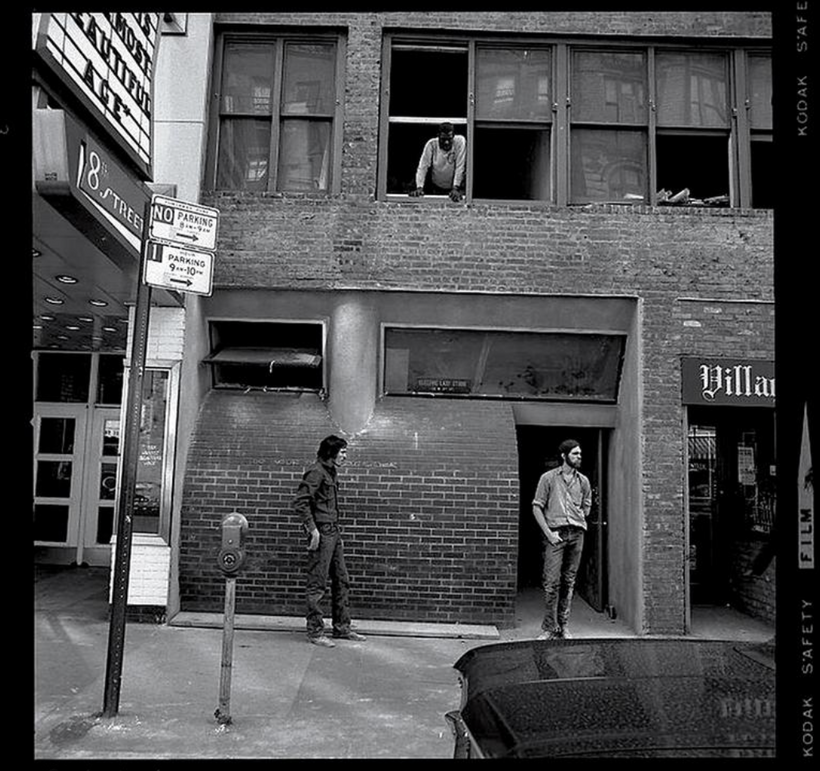

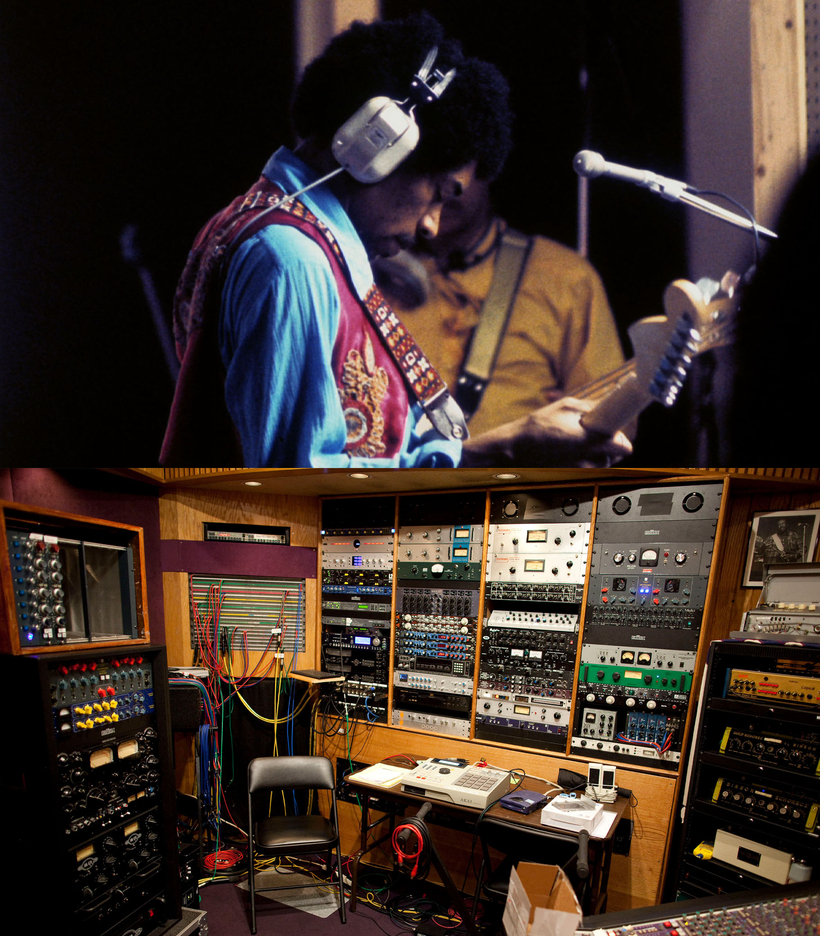

Electric Lady, on Manhattan’s West Eighth Street, in 1970, the year it opened.

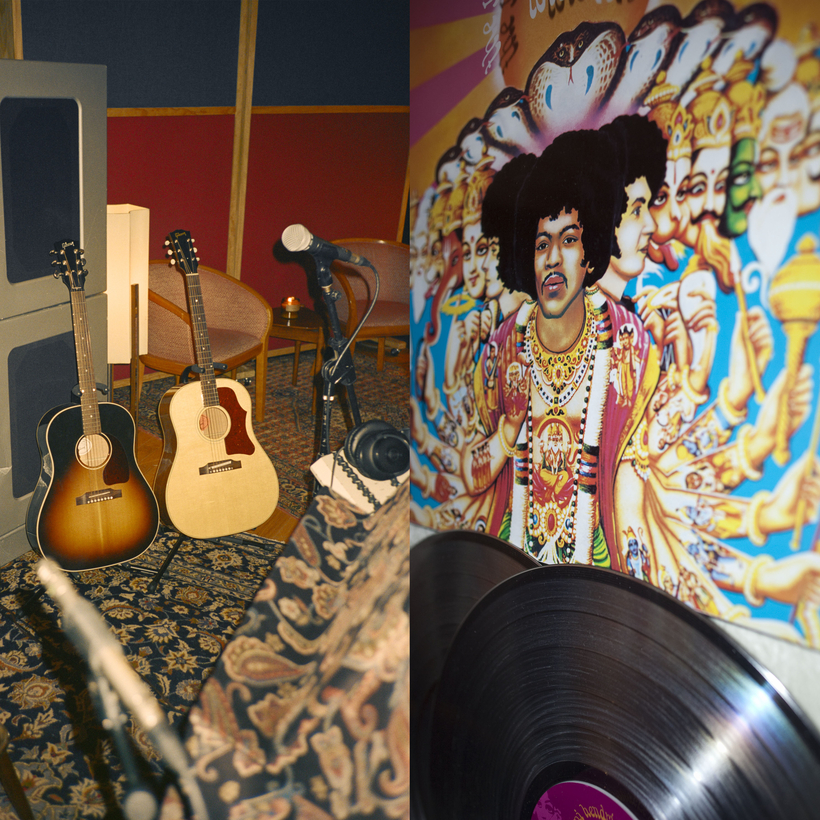

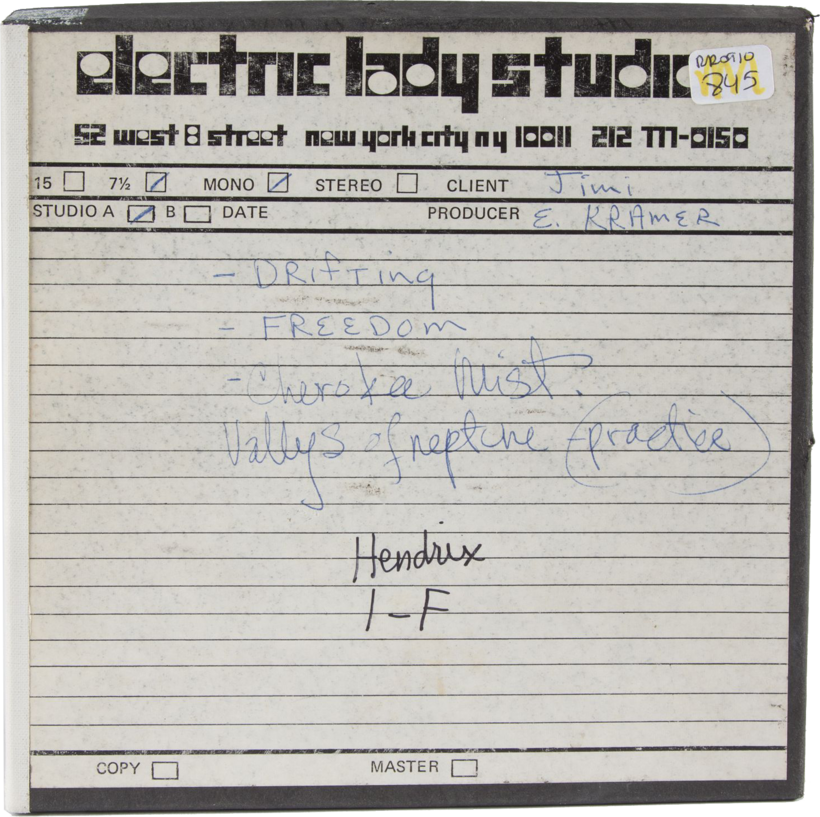

A reel-to-reel recording of “Drifting,” “Freedom,” “Cherokee Mist,” and “Valleys of Neptune,” produced by Jimi Hendrix at Electric Lady Studios in the months leading up to his death.

The idea was hatched in 1968 by Jimi Hendrix and his manager Michael Jeffery when they bought a newly shuttered nightclub called the Generation, at 52 West Eighth Street. The plan was to rename the club and continue with the live venue, but advisers Eddie Kramer and Jim Marron talked Hendrix into flipping the space into a proper recording studio.

Top, Hendrix at Electric Lady; above, the recording equipment inside Studio B.

Named after Hendrix’s seminal 1968 album, Electric Lady was the only artist-owned recording studio at the time. In the 1970s, it played host to countless legends, from David Bowie and the Rolling Stones to Stevie Wonder and Patti Smith. Electric Lady Studios was the location of Hendrix’s last-ever studio recording—an instrumental known as “Slow Blues”—before his death, on September 18, 1970.

My fascination with the place goes back years and years. The idea of something so rich with history continuing to thrive when things can be done in a much cheaper way is intriguing.

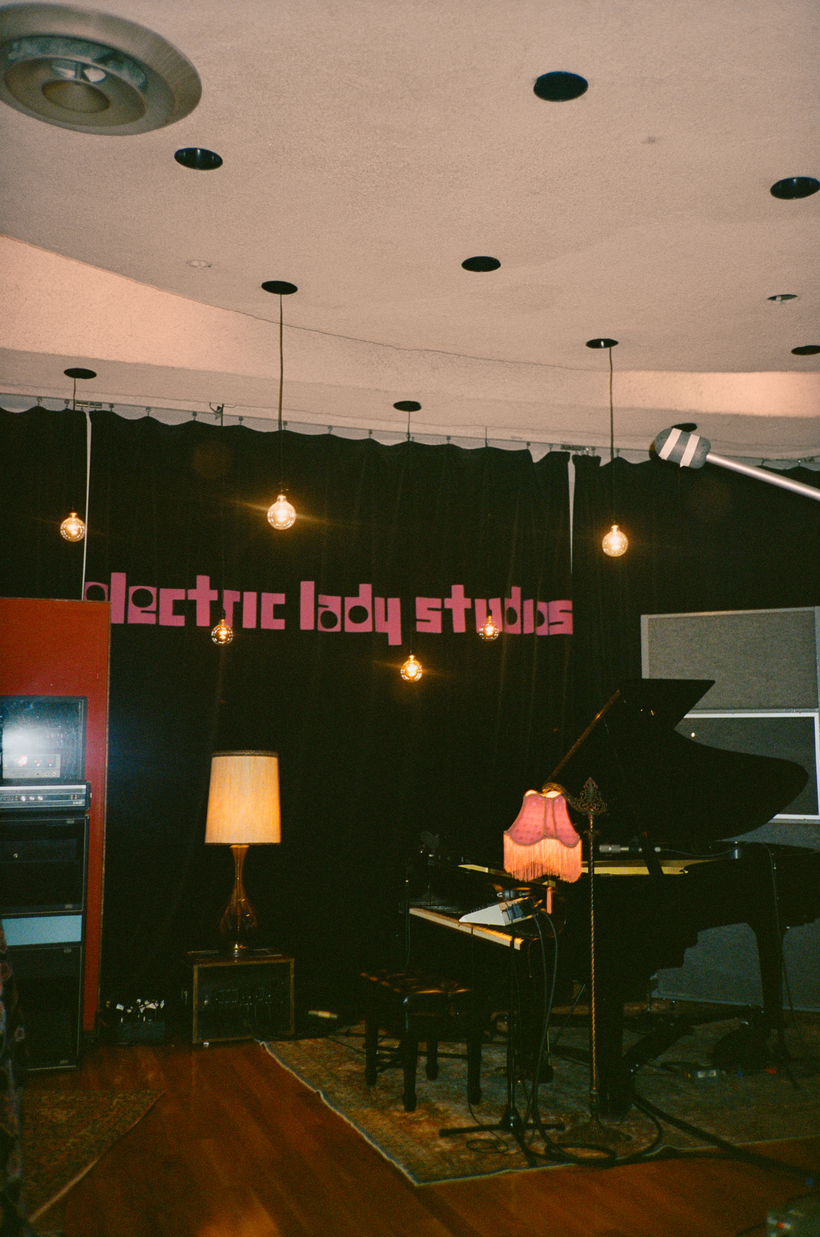

Electric Lady, photographed last month by the author.

Designed by a fresh-out-of Princeton architect named John Storyk, the curved surfaces, colorful murals, theatrical lighting, and porthole-style windows inside Electric Lady give the space a distinct feeling. In 50 years, not much has changed—including the signature mirrored outer windows, which Storyk also designed—but now the studio is owned by the investor Keith Stoltz and longtime studio manager Lee Foster. Walking into the A room a few weeks ago, I had the idea of being physically in New York City but mentally somewhere—and some time—totally different.

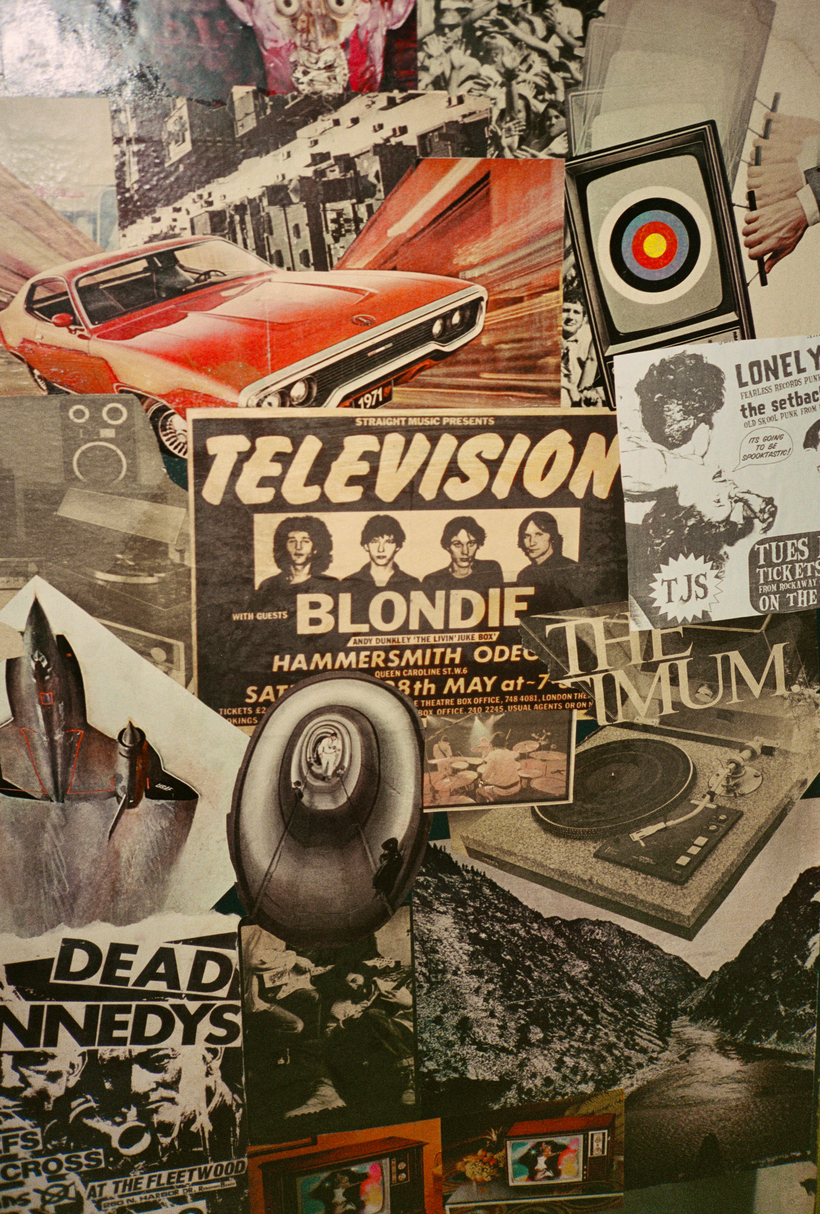

Posters like these line the walls of the space.

Mark Ronson, a record producer and songwriter who grew up in New York City, had his first Electric Lady experience in 1999, while co-producing an album for Nikka Costa. While tracking drums with Questlove, Ronson tells me, Common would come to hang out in the lounge, and Erykah Badu would roam the halls. “These people were already legends to me, so the whole thing was quite surreal.”

Ronson has clocked countless hours at Electric Lady and thinks that the history is not only part of the magic but a driving force that encourages artists and producers to rise to the occasion. The walls tell the story of the place, from the oversize Patti Smith poster that greets you as you walk down the stairs to a D’Angelo Voodoo plaque and a wall collage with a handbill advertising a show where Blondie opened for Television. “It’s not like you’re guaranteed to make quality shit when you step inside,” Ronson says, “but there is an extra sense of wanting to be better.”

The studio’s history encourages artists and producers to rise to the occasion.

The draw Ronson felt in the late 90s has not diminished. Frank Ocean, Maggie Rogers, Jon Batiste, and Bad Bunny have all made records you probably know on West Eighth Street. “Once you descend those stairs into Studio A or B or head up to Studio D,” Ronson says, “it feels like a musical sanctuary.”

Fifty-plus years later, the intended magic still emanates. “Electric Lady is its own universe.”