Vinyl is hot — again. So is Trutone Mastering Labs, a vinyl record-cutting studio born 50 years ago in a North Jersey basement. When co-founders Carl and Adrianna Rowatti moved to Orangeburg, New York, the studio moved with them.

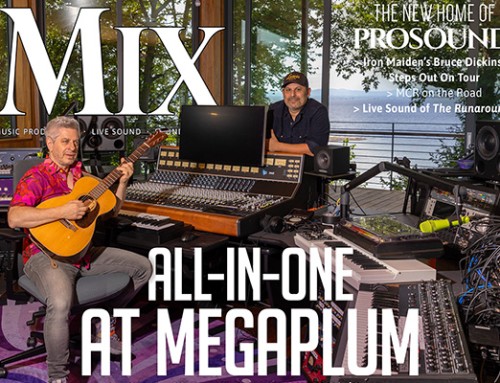

PERFECT HARMONY Adrianna and Carl Rowatti, co-founders of Trutone Mastering Labs; designer/architect John Storyk with Rowatti in the studio.

They brought a wealth of experience, a collection of top-of-the- line equipment and a penchant for quality studio design. After gaining its footing in vinyl and preserving it as its keystone, Trutone

is well positioned to meet the growing demand for analog mastering and vinyl cutting. The company’s operating space is modern, quite a step up from its humbler origins.

Spotless and shaded in muted grays, Trutone’s mastering suite shows the thoughtfulness that went into its construction.

The looks come secondary, however. The main goal is to create the ideal space for sound clarity — and for turning a rough mix into a cohesive track.

The studio is one of nearly a dozen customized by the Rowattis over the decades, locations in Haworth and Hackensack among them. They also restored the New York City studio where John Lennon recorded on the day he was shot and killed.

Each has been meticulously configured. Studio walls are decoupled from the structure to form “a box inside a box,” says John Storyk, a renowned studio designer and architect based in New York City who designed Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios in 1970, and worked on the Rowattis’ last two spaces. Diffusers and membranes are strategically placed out of sight to further manage sound frequencies, limiting low-frequency vibrations and improving overall quality.

The Rowatti’s studio houses new technology as well as vintage gear.

Carl concedes that his studio setups could be considered overkill. “It depends on the level of sophistication that you’re looking for,” he says.

Trutone’s clients are renowned. Trutone’s credits include Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Whitney Houston, Luciano Pavarotti, the Smashing Pumpkins, the Killers and the Rolling Stones. Most of them contract with Carl for his high level of experience and skill. They also come for Trutone’s rare museum-quality analog equipment.

Some of Carl’s gear is more than 50 years old — not the latest, yet, with bespoke tonality and personality, among the greatest. His Fairchild 670 tube-based compressor, for example, is the superior, dual-channel version of the famed 660 favored by

The Beatles in the 1960s.

At that time, Carl was a teenager who cut one-off records on the Presto 6N lathe of his father, Lou Rowatti. Lou, effectively the inspira- tion for Trutone, recorded weddings and sold newlyweds custom-cut albums. He also lent Carl and Adrianna $1,000 to start their company.

This photo gives a view of the lathe-cutting equipment to the right of Rowatti’s mixing position.

In Trutone’s infancy, Carl would show up at local schools and churches to record concerts they could turn into records. Adrianna sold albums to cover their costs. The profits went toward new equipment. “The time we would have spent in col- lege, we spent building Trutone,” Adrianna says.

For three years, the business was a side hustle. They ran it out of Carl’s childhood home; that North Bergen basement was just 10-foot square. By 1975, the business had grown enough for the Rowattis to quit their day jobs. Married now, they went full-time and moved to Northvale. Their new in-home mastering facility became their calling card.

Stanton Magnetics, a company that makes high-end DJ equipment, called them about participating in a national advertising campaign. The Northvale studio was soon infiltrated by staff at audio publications, from High Fidelity to the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, who were curious about their sanctum’s inner workings. Their popularity and Adrianna’s pregnancy forced a quick expansion.

Trutone opened its first commercial facility in Haworth in 1976. First, it spilled over to the space next door. Later, it extended across the street. The company then specialized in cutting master lacquer discs for producing vinyl records. CDs would come in 1984, and volumes swelled.

In 1990, Trutone’s business forced them into an empty 15,000-square foot warehouse in Hackensack. A yearlong build-out created master- ing studios, modern offices, a graphic art depart- ment, a cassette duplication and a fulfillment factory. A CD packaging division was later added.

The expansion may have been Trutone’s high point. “I can’t believe how brave we were,” Adrianna says. At its largest, Trutone had 37 employees. Today, Trutone is the original two, Carl and Adrianna Rowatti, plus an off-and-on intern. They say the lack of a corporate board has allowed them to easily shift along with industry trends. “We moved with the demand and kept a tight eye on expenses,” Adrianna says. “We had to. It was our baby.”

The duo displayed their adaptability with a related business, Music on the Run, in Manhattan. The small CD and cassette production shop opened in 1999. It catered to studios, artists and other customers seeking short runs with custom graphics in a few hours.

Experiencing the increased traffic and presence the New York operation provided, the Rowattis decided in 2002 to relocate their mastering studios to Manhattan. They found a 10th-floor studio on West 44th Street two blocks from Music on the Run. The rundown studio turned out to be the Record Plant.

First opened in 1968, the Record Plant was originally styled as a recording studio for full bands. Its first customer was The Jimi Hendrix Experience. Its first album, Electric Ladyland, was the band’s last. Other acts, including Miles Davis, Aerosmith and The Who, recorded there before it closed in 1987. Storyk says that converting the expanse to a mastering facility came with challenges. It was nonetheless easier than his next project with Trutone in 2008 — cramming a studio under 9-foot ceilings into the Rowattis’ Rockland County basement.

That project came without much warning. Sony BMG Music Entertainment had recently closed its 54th Street studio complex amid the recession. Trutone offered Sony officials exclusive use of one of its 44th Street mastering suites. Sony countered with a buyout offer.

Adrianna says it was one of those things you just can’t refuse. By then, the Hackensack facility had been closed for three years due to dwindling cassette and CD sales. Meanwhile, a competitor wanted to take over Music on the Run. The couple says they happily made a retreat to Rockland County. Adrianna admits she misses the Manhattan penthouse. Storyk calls the move a stroke of genius. “(Carl) got ahead of the curve and realized he should get out of Manhattan and do this in his home,” says Storyk. “He was about five years ahead of the curve.”

Since the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, mastering has become a more isolated craft. Artists rarely sit in on sessions. Albums are often made by more than a dozen different content creators, with each working independently in far-flung studios. Someone has to make the album sound cohesive, Storyk says. That’s where Trutone comes in.

The mastering continues daily. So does the vinyl cutting. Carl says he appreciates the short commute after 50 years in business. The work flows in, sometimes in floods. “He’s going to have as much work as he wants until he doesn’t want to work anymore,” Storyk says. “Carl has made

a niche in vinyl. It’s a dying art but a growing need.”