Peter D’Antonio Talks Studio Design, 40 Years of RPG and a Lifetime of Science and Sound.

BY TOM KENNY ⋅

Today, anybody from anywhere in the world can pick up their phone, download an app or visit a site, enter a few numbers, wait a few minutes for a recommendation, click on a package of acoustic materials, and a week later, once the packages arrive and the panels, cylinders and clouds are placed on the walls and in the corners, their personal studio immediately sounds better.

Results, of course, will vary depending on the quality of the app, the amount of data entered, the boundary limits of the space, materials in the walls, floor and ceiling, speaker location, whether there is follow-up measurement included, and dozens of other factors. Still, the simple fact that the sound and performance in a personal space can be dramatically improved by entering a set of data points is remarkable.

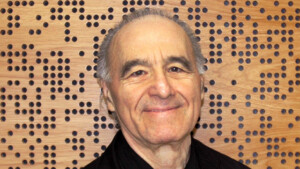

This didn’t just happen overnight, or because some kid in Silicon Valley had an idea. It’s all possible because of science. Real science. Decades of theory, test and measurement by a relatively small number of individuals at universities, in laboratories and at home. Dr. Peter D’Antonio is one of those individuals—but he’s also a scientist who plays bass guitar. His name is not always included when conversations turn to the great studios of the world and those who designed them, but when the top studio designers get together, D’Antonio has a seat at the head of the table—though his humble nature and sociable personality would likely force him to get up and move down near the middle, among his friends.

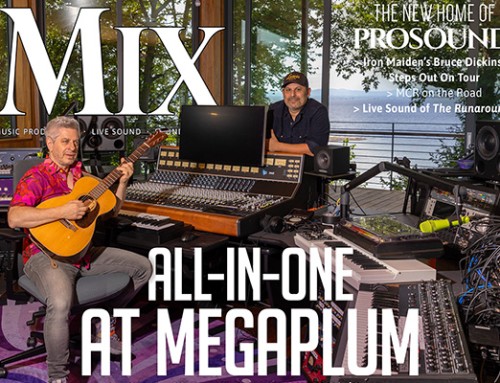

Over the past 40 years, following the establishment of RPG Diffusor Systems in December 1983 and through his ongoing collaborations with the world’s top studio designers, D’Antonio, as much as any single person in professional audio, has helped to shape the look, feel and performance of the modern recording studio.

This year, D’Antonio is earning his just recognition, with a 40-year anniversary celebration of his original company, a highly anticipated AES Paper presentation later this month, and the honor of receiving the prestigious Wallace Clement Sabine Medal from the Acoustical Society of America for “contributions to the theory, design and application of acoustic diffusers.”

It’s been quite a ride. D’Antonio never planned to study acoustics or become the world’s leading expert in diffusion, or what he sometimes calls “the scattering of sound.” Born and raised in a middle-class, working-man Italian neighborhood of Brooklyn, his interest in music was nurtured by his mother and uncle, both outstanding vocalists, he says. He played in bands in high school, gigging through the summers at the Long Beach Resort, developing an early fondness for harmonies and doo-wop.

Then, admittedly having never really applied himself in school, he went to college, majoring in physical chemistry at nearby St. John’s, followed by a graduate degree in infrared spectroscopy, with a minor emphasis in crystallography, A professor recommended him for a job at the Naval Research Laboratory, and in 1968 he moved to Washington, D.C., leaving his musical life behind. Then in 1970, he lost his wife in an accident.

To deal with the loss, D’Antonio says, he slowly began to bring music back into his life, hooking up with a next-door neighbor to jam and write. They built a rudimentary, single-room studio in his house and dubbed it Underground Sound. The songs got better, the playing got better, but the recording quality was noticeably lacking. In the early 1980s, D’Antonio proposed building a better studio, one with a separate control room and proper isolation. At the time, he was still working at the lab and had zero knowledge of acoustics— studio, architectural or otherwise—but he was a scientist, he could figure it out.

And that’s where we begin this month’s special Mix Interview.

So this lifetime spent in acoustics all began because you wanted better recordings? There were some good studios out there in 1983.

I had a typical two-story, suburban neighborhood home with a sub-basement that would work as a studio, but I had absolutely no idea how to build one. I hadn’t thought about acoustics for one second of my life before that. How do we even soundproof this room? I went through the literature, like all scientists do, and found you have to float the room and all that good stuff. Then we spent about two years on the construction, the AC, the plumbing, the air conditioning, the wiring—everything by ourselves.

The problem was there was no control room. For a lot of studios at that time, the speakers were still hanging from chains and the rooms were not symmetrical, which you need for an effective soundstage. I had seen a booth at another studio, and that’s when I thought, “Well, how do we design a control room?” I went to the literature, and there was absolutely nothing. All I could find was articles on how so-and-so had a hit record and used this kind of speaker, and then everybody copied that design.

Then I came across an article by Don and Carolyn Davis and it actually sounded scientific, talking about the principles of Live End Dead End. They were using a device that I had never heard of, developed by Richard Heyser, called time delay spectrometry. Richard worked at Jet Propulsion Laboratory and he was a brilliant guy who was interested in audio. He would measure loudspeakers for audio magazines, and he developed this hardware that originally had about 15 pieces of gear with wires and everything. Then Crown built it into what was called the TEF Analyzer.

Anyway, I built a room and I implemented Live End Dead End. I put some pressure on the wall in the front, and I had a bare back wall, but when I listened to the room, it was very disappointing. The interference between those strong specular reflections and the direct sound was severe.

What did you do?

I decided to take the approach of, “What if I just came down from Mars? What would I do?”

I started researching concert hall design. There’s an important aspect of a concert hall in that you have the direct sound, and then there’s a period of time, which is called the initial time delay, before the reflections come in from the side walls. I say side walls because in the early concert hall designs, the ceiling was a lot higher than the width of the room, so the first reflections that came into the room came from the side, but because the speed of sound is finite, it takes time to go from the stage to the side wall to the audience—this initial time delay. How in the hell can I get an initial time delay in a small room when there is no time delay between the sidewalls and the speaker?’

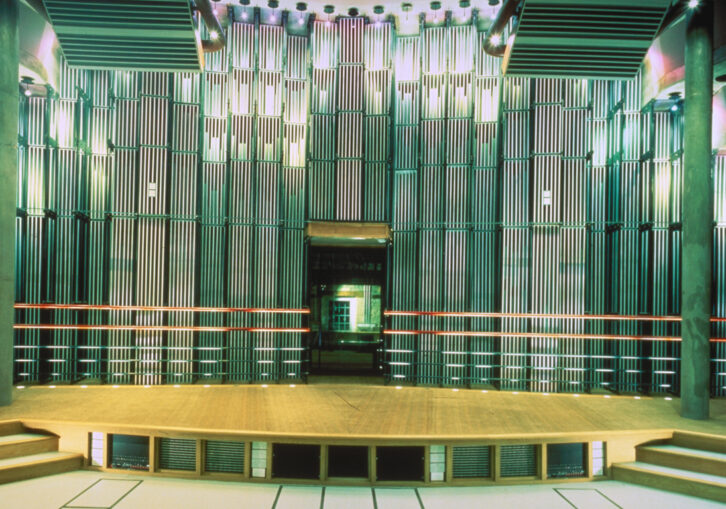

That’s when I came up with this idea of a temporal and spatial reflection-free zone, where I splayed the sidewalls out so that the reflections from the loudspeakers hit the sidewalls and went to the back of the room. It didn’t come to the listening position. Then I also slanted the ceiling vertically at an angle so that those reflections would go to the back of the room. That has become the signature of all control rooms to this day—but now that sound is going to bounce back and cause problems at the listening position. How do I constructively control that real-world dance? The answer was diffusion.

So the back wall of the studio in your basement is what led to RPG Diffusor Systems?

[Laughs] You could look at it that way. During my research, I came across an article by Manfred Schroeder in Physics Today’s October 1980 issue. It described reflection phase grating (RPG) diffusors that were capable of uniformly scattering sound, and I realized that these diffusors were 2-dimensional periodic versions of the 3-dimensional periodic crystal lattices I had been studying as a diffraction physicist at the Naval Research Lab, using x-ray crystallography. That led me to further research and my first acoustical presentation at the 74th AES Studio Design Session C in October of 1983 in New York. To my surprise, Manfred Schroeder presented the leadoff presentation.

Anyway, because these diffusors scattered the sound and because the reflection was not in one direction, all of the energy in that reflection was now distributed to all of the reflections. So the sound that came back to the mixing position was attenuated, but the sound remained in the room, The room remained ambient.

I needed to control those reflections to create the reflection-free zone. I realized that the diffusor in the back of the room was sending sound out over a semicircle in the back of the room, and a lot of the sound was hitting the sidewalls, so I made the sidewalls reflective and they reflected the sound back to the listener at 55 degrees, so when you go into a room that has reflections diffused on the rear wall, you get a sense of envelopment. I didn’t realize it at the time, but we had created what’s called passive surround. That’s when the high-end audio community became really interested in diffusion.

Do you mean studio owners, studio designers, other acousticians?

Don Davis was at my AES presentation, and after the meeting, he introduced himself, saying that he taught acoustics and that he and his wife Carolyn had these traveling roadshows around the country. He invited me to their next meeting in Dallas, the first on LEDE, and asked that I bring my diffusors. I thought, “Okay, this is great”—but I didn’t have any.

We built two—and they were big. We shipped them to Dallas for the Syn-Aud-Con event, where they had a TEF Analyzer. That was the first measurement of the time response of these units. As we measured, I thought, “Wow! That’s what they should do!” What intrigued me was that we could actually see on the screen all of the reflective sound—when it arrived, what level it was. I thought this was fantastic. Bob Todrank was there, and Don Davis. They basically befriended me and introduced me to the world of acoustics.

Bob owned Valley Audio in Nashville at the time and he said, “You know, I got this job for the Oak Ridge Boys in Hendersonville, and I like what you’re talking about. You want to collaborate with me?” I said, sure, though at the time, I really couldn’t manufacture anything. I basically provided him with plans, and in 1984, the Oak Ridge Boys’ studio was the first commercial project to incorporate RPG Diffusors. The next Syn-Aud-Con meeting was held there, and that’s where I met Russ Berger. The first studio he did with RPGs was called the Dallas Sound Labs; we put a whole array of 4311s in there, and that became a really successful room. I also met Neil Grant at that Oak Ridge Boys event—later, I would do Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios with Harris Grant in the UK, and Neil became probably my closest friend.

Continue to Part 2 here.