Noted acoustician and architect has improved sports sound, both in-venue and broadcast.

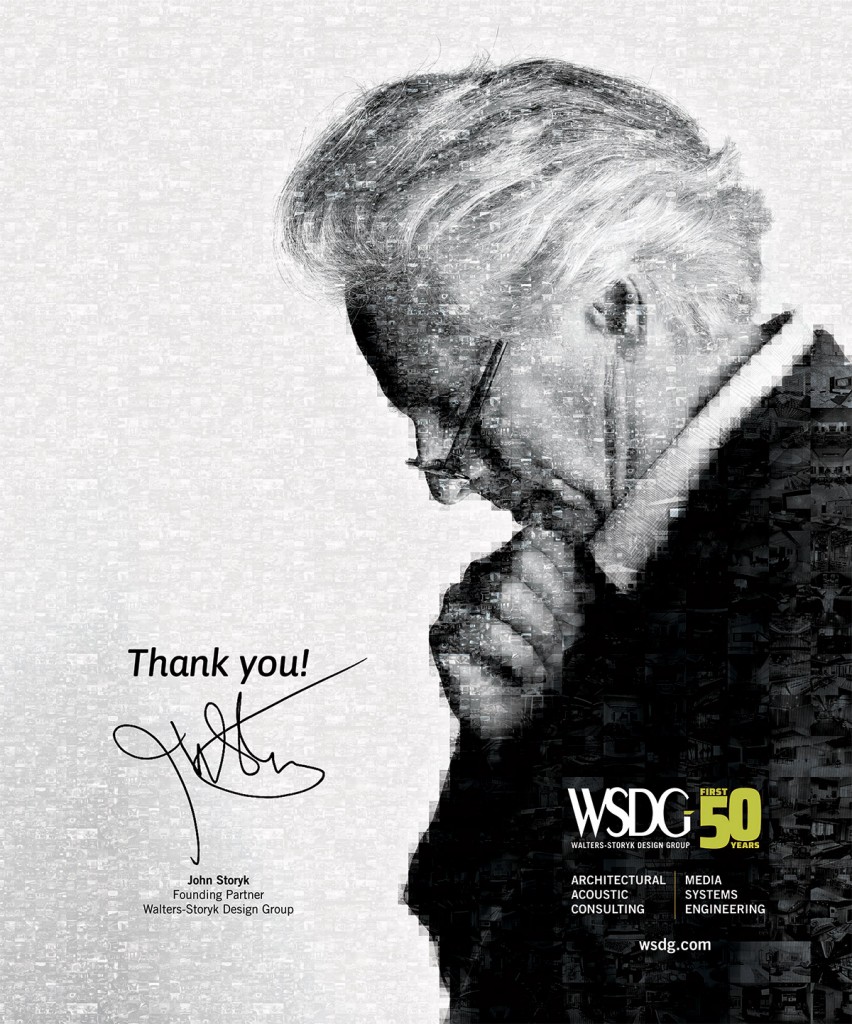

The thought of celebrating a 50th anniversary makes architect/acoustician John Storyk slightly ill at ease, as he approaches the half-century mark of a career that has helped improve the sound of scores of sports and broadcast venues globally. However, when that milestone is amended to simply commemorate the “first 50” years, he feels a bit better: there’s still a lot that he would like to do.

His company, WSDG-Walters-Storyk Design Group — a decentralized alliance of associates in North, South, and Central America and Europe — continues to expand. In 2017, WSDG acquired Berlin-based ADA, a leading European acoustical consulting firm, and 40% of his colleagues are under 40 years old, so the company has plenty of headroom in its knowledge base but remains anchored by Storyk’s storied legacy.

He is most celebrated for designing and building Electric Lady Studios, his very first project and the home base for Jimi Hendrix when it opened in 1969. It was serendipity that connected the guitar icon with Storyk, who had musical ambitions but was looking for traction with his newly minted Princeton degree in architecture. Since then, his portfolio has grown to cover elite restaurants, high-end music venues, iconic recording studios, and multimillion-dollar homes — and a sports-venue collection that includes Estádio Jornalista Mario Filho (popularly known as Maracanã), the biggest soccer stadium in Brazil, site of the 2014 FiFA World Cup, and home to Opening and Closing Ceremonies of the 2016 Olympics; the Arena Thun venue in Switzerland; and the Barra Olympic Park, developed as Rio de Janiero’s primary 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games site.

Next on the agenda, a 4,000-seat theater to be appended to Boston’s Fenway Park, giving that storied ballpark a place to host esports events. Storyk is also working on a 53,000-sq.-ft. esports arena that will be part of Velocity Arts, a planned $500 million destination campus in Kansas City.

Figuring Out Formats

Storyk’s career has spanned audio formats from mono to surround, but he considers immersive-sound to be the most exciting of all, not least because it’s still figuring itself out.

“It’s like the Wild West,” he says. “It’s still trying to figure out what it wants to be. It still needs to be better defined for sports, like it has been for movies and TV. The big guys — Dolby and Auro and others [WSDG favors the Barco-owned Auro format, which Storyk prefers for smaller-room immersive monitoring] — are fighting it out for standards and market share, and there’s a lot of money at stake. But, in the end, it’ll be great, because immersive is the closest we have come to be able to reproduce the world the way it sounds, as we actually experience it. For the first time, you’ll be able to feel like you’re actually in Yankee Stadium when you watch the Yanks on television.” (Storyk is a die-hard Bronx Bombers fan.)

Immersive sound will impact sports audio, both for broadcast and in the venue, Storyk believes, and sports’ live sound has already evolved dramatically since he began working on sports venues. But he also cautions that, while spiraling costs are compelling new venue designs for multiuse applications, from sports to concerts to trade shows and other uses, a venue should emphasize a primary purpose.

“A ballpark should be a ballpark first, a stagehouse second,” he says. “They can be good at both but not necessarily great at both.”

Storyk stresses that advances in audio technology ought to be leveraged as much as possible for sports venues. Such advances include networked audio, for the flexibility it offers designers, and auralization software, which can do predictive virtual analysis of how sound will behave in a space, for its ability to discern problems before they get set in concrete. He cites how auralization enabled his team to head off significant reflections in a stadium at the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio. Now several listening studios in WSDG’s offices allow clients to sonically “preview” the sound of their yet-to-be-built venues to get a sense of what various audio-system components will sound like in it and how different materials can affect the ambient sound.

“Sports venues in general are paying more attention to sound and acoustics now, and that’s good,” Storyk says. “The industry has learned that they can’t just build boxes and charge $225 for a ticket to see a game. Fan expectations have increased, not only for sound but also for being entertained in general in the stadium or the arena.”

“Think about it,” he continues. “At least a third of the time sitting in the venue, if not more, is all about what’s on the big screen and in the PA system, during breaks in the action on the field. That’s where we try to make the overall experience of going to the game, of being in the stands, as good as it can be. That’s part of our job.”