Messages in Bottles

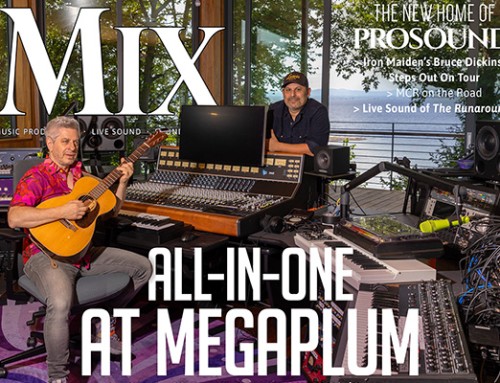

BY BREN DAVIES | PHOTOGRAPHS BY BRIAN T. SILAK

Download Full Article (2.5 mb)

Born in Bergenfield, New Jersey, Jack Antonoff has performed, recorded, and toured with the bands Outline, Steel Train, fun., Bleachers, and, most recently, Red Hearse, with a self-titled album released in 2019. He has co-written with (and/or produced) Taylor Swift, St. Vincent [Tape Op #134], Lorde, Lana Del Rey, Carly Rae Jepsen, Pink, and Sara Bareilles – basically a Who’s Who of recent pop stars. He’s won four Grammys, and he’s even started his own music festival, Shadow of the City, in New Jersey. He produced the soundtrack for the 2018 film Love, Simon, which includes four Bleachers songs. Brian and I caught up with Jack at his Walters-Storyk designed home studio in Brooklyn, NY.

You maintain a busy writing, recording, performing, and touring schedule, with multiple simultaneous projects. Is it ever hard to keep track of so many events?

When you read it like that, it sounds like more than it is. At any given time, I actually consider myself to have less going on than a lot of other people I know who do what I do. It’s because the focus is on albums. Me and Kevin Abstract made an album that took a month [ARIZONA BABY]. Right now, I’m making an album with the Dixie Chicks that’s going on two years. If you make albums, you can do different projects at once, because it’s more of a meditative thing – it’s all-existing. I’ll be working on one project and think, “Okay, these songs need help,” and then I’ll spend a couple of hours there. I’ll go into a session with these people [whom] I’ve been working on this long project with for a week, and then everybody goes their separate ways. You take a step back. To have these ongoing album projects, it actually enables me to jump around more, because they’re living and breathing. They’re almost like family. How do you have time for friends and family? Well, I don’t spend every day with them. If I go on vacation with my family somewhere, I’ll be focused and spend time with them. Then I’ll come back and spend time with my girlfriend, and I’ll be focused and spend time with her. I think that’s what albums are. It comes up a lot where people have this idea that it’s this crazy output, but sometimes these things take a long time. Sometimes they line up where it seems like they’re just firing out, [and then] there’s a period when nothing’s coming out. I’m in this period now where a lot of records are coming out.

You appear to be continually productive.

I sleep eight hours a night. I travel and tour a lot. I try to put the focus on the bigger picture and not get too lost in the minutiae. That’s what it’s all about. Making records, albums, songs – anything – I make it so it feels good, and I’m not convincing myself that it feels good because of how I did it. I get all the way under the hood and do it in a way that feels interesting – if you want to put that microscope on it. Obviously, you guys [Tape Op] are gear-related. You can have everything dialed in perfectly; the greatest gear in the world – the board they did this on, and the mic they did that on. They’re tools to get you somewhere. You want to have all that going so that if magic happens, you capture it in an exciting way. I’ve been in a lot of situations where something magical happened, but it wasn’t captured well.

You’ve said that the whole point to writing songs and making records is to relate to people. How does Jack Antonoff relate to his fans through his music, his songwriting, and through his productions?

I don’t think that the point of writing songs and writing music is to relate to people. I might have said that, but I actually think that the point of releasing music is to relate to people. A lot of times, I write and record music I don’t intend to release, and I’m doing it to feel myself. Maybe the long-term goal is to find an interesting bass line that’ll go somewhere, but I’m just having a good time. Releasing music is an act of throwing a message in a bottle and sending it out into the ocean. The nature of releasing music – and writing and recording music that you know you’re gonna release – is somewhat a cry for help; but really it’s more like a call. It’s like shouting, “Does anyone else feel this way too?” Everyone’s DNA comes out in everything [they record]. For example, the way you EQ a mic: are you someone who wants to have it bright and have [the listener] feel like they’re talking right to you? Do you want it to feel distant? It’s fascinating how all these things are expressions of the soul. To release that music; you’re trying to find your own little tribe, your people who hear it. Take Nine Inch Nails: all of those albums sound a very specific way, even the ones that are a departure. Or David Bowie, who made so many different styles of music; there’s still this common thread that if you get it, you get it. Releasing music is just asking if anyone’s having a similar experience to you. That’s why so many people who make records didn’t relate super well early in life – at least a lot of people I know. They use this medium to find people all over the world, because maybe in their small town they didn’t find enough people.

What was your first recording setup like?

When I was in my house in New Jersey, I had a laptop. I had a [Shure] SM7 going right into the interface – not going through anything. I think it was the first Mbox. I was recording on cassette when I was a kid. I was always super into recording. When I was 12 years-old, I was taping everything. I recorded my band called The Fizz from ‘97. Early recordings were on little cassette recorders. Then I saved up and got this weird Zip disk recorder, the Roland VS-840. It was massive, and the latency was out of control. It was almost impossible to multitrack, but I did. From there, [I worked with] local studios that had ADAT. It was that super shitty phase of recording when it was post-tape and pre-Pro Tools. At some point, that first Mbox came out. I recorded on that forever. At that point, I had no concept of anything. I’d turn the knob until it hit red. I’d only seen Pro Tools in big studios. There was this guy named John Naclerio at Nada Recording in Newburgh, New York. He would record us and let us come in for a month for $1,500. It was on ADAT; punching and punching to try to get the punch right. Why weren’t we recording on tape? Obviously, it was the cost issue. Then he got Pro Tools, and it was mind-blowing. My old band, Outline, was his first Pro Tools recording. It was so cool because of the options.

You’ve recorded in L.A., Atlanta, New York, and other cities, and have spoken about differences in the vibe, sound, and feel from city to city. When you’re not working here in your home studio, what are some of your other favorite places?

When I was growing up in New Jersey, I would move the recording session to my room, to the basement, to my sister’s room, to the living room. Spaces are important, and you can burn them out. At one point, I burned this space out, and now I’m falling back in love with it. I did a number of records in a row in here. I started to hear myself repeating myself, because it almost gets too easy and everything’s good to go. I love Electric Lady Studios. I’ve been spending a ton of time there. I have a room at Electric Lady, so when I’m in New York I bounce back and forth between here and there. Electric Lady’s one of the greatest places on earth – it’s one of the most important studios, historically. It’s an honor to be there. You get to walk around in [Washington Square Park] and think. The park is very unchanged, by the nature of college students and drug addicts always being themselves no matter what’s going on in the world. I spend a lot of time there. In L.A., I’m usually at Conway [Recording Studios], which is also one of my favorite studios in the world. Every room there has a Neve [console] that I love for different reasons. I spend time at Henson [Recording Studios, formerly A&M Studios]. That’s a great place. One place I’m dying to go to is Candy Bomber in Berlin. I heard about it from Nick Cave’s people. I saw them recently at Conway, and they were saying how brilliant [Candy Bomber] was. There’s a studio called La Fabrique in France, where they do Mix With The Masters. I want to check that place out. I try not to go to big studios, unless I go somewhere for a specific reason. Obviously in L.A., I’m at a [big] studio. I took the band up to a place called Outlier Inn in upstate New York, which is an interesting studio. In Atlanta, we were at Atlanta Doppler Studios – a wonderful place. I’ve worked all over the world, and I basically work every day, so I almost see it like gathering. It’s more about working in the quiet of a hotel room, or finding bizarre sounds in the town, and bringing that back [to the studio]. If I’m out traveling, I’ll record as much as possible, go to my hotel room, do a ton of editing, and then bring it back to here, Electric Lady, or Conway. I’ll sift through and decide in those spaces, where I know what it sounds like. My whole plan with a room is have it ready to go and have tricks everywhere, with mics in every corner; no fiddling, and I can have options. Picture this: you’re sitting at the piano, so we’re going to record stereo mics on the piano, obviously. But then why not also throw up that Telefunken and the Wunder Audio CM7 because we’re doing vocals all over the room? My favorite is a [Rode NT5] stereo pair, which gets the coolest room sound. Now you have one piano take, plus all these other possibilities that, if you didn’t have, you would sit there and try to create with plug-ins. This doesn’t break the bank; we’re not talking about crazy mics. It’s about options. Then you can bleed them together, or set them off of each other by a few centimeters. You can send one through some tape echo and keep another one dry. Any space that I build is just options, to get it all and then figure it out later. I can’t tell you how many times the piano sound on a record has been from those two mics up there [pointing to Rode NT5s]. Or the guitar sounds; we had this one mic on guitar, but the CM7 in the corner got the cooler sound. The downside to that is that you can get locked into certain sounds, but that doesn’t happen too often.

You’ve spoken about a certain darkness and melancholy that seems to inform a lot of your solo songwriting, your cowriting, and your production. A big part of this comes from the passing of your sister [Sarah, who passed from brain cancer when Antonoff was a senior in high school]. Are there any other places within your life that inform this melancholy?

I think we all have it. For a long time I would brush things under that rug and be like, “Oh, I’m sad and introspective because of this loss.” That’s bullshit. Everyone is having their own version of a hard time. This work that we do is a function of figuring that out. We’re not people who make something tangible or specific. [This process] is an emotional tool. Every side of it is about getting to the bone of something. Happiness is pretty uninspiring, historically – and specifically in music. What’s inspiring is taking the darkness and trying to sift through it. Happiness, or having a great old time – well, we all know what that feels like. If you pull up any playlist you have, even ones you don’t think are particularly dark, what’s way more interesting is sifting through the darkness where you can’t find your way and can’t make sense [of anything]. When I was younger and was going through grief and loss, I thought, “Oh, I’m out here on an island reporting about this thing that very few people can relate to.” The older I get, the more I realize it was always going to be that way. Everyone I know and relate to in this work seems to come from that space of just sifting through darkness. Even songs about feeling good are about darkness, because they are all about “when I didn’t feel good.” The best example of that is Christmas music. Every Christmas song ever is, “I hope my baby comes back on Christmas. I hope I’m not alone next Christmas. I hope I survive.” It’s always a twist. Even the happiest songs still have that tinge of “maybe it’ll go away.” It’s the fabric or thread that connects all of us, and that’s what we do. Music is meant to connect.

You’ve said in interviews that “if you live in the suburbs, you dream. If you live in New York City, you’re not dreaming, because you’re there.” Or, “Growing up in a place that is forced to be in the shadow of something is really special, because there’s so much energy in that.” What was it about growing up in the suburbs that has had such an influence on you and your music?

Your lyrics, your chord changes, the notes you gravitate to, and the sound you gravitate towards – your whole sound – is based on where you’re reporting from. If you’re reporting from a town in the middle of nowhere, that’s a perspective. If you’re reporting from the center of New York City, Hollywood, or London, that’s a perspective. That changes things, and you hear it in the songs. My perspective, and the place I report from – I lived there my whole life, and it’s ingrained in me – is a specific place. It’s New Jersey; and what’s so specific about New Jersey is its proximity to one of, if not THE greatest city in the world – and the almost medieval cruelty, where there’s this thin body of water that separates [the two]. So, it’s not the same as being from “near the city.” It’s very specific, and it creates what I’ve come to know as “the New Jersey sound.” It’s staring into the window of the party. There are these feelings in New Jersey of, “We’ve gotta get out of here.” But there’s more to it than that, because you get these East Coast sorts of sounds. You feel that in some of the changes in the horns, [and] there’s such a melancholy to it. Then you go further up the coast, and it gets a little bit brighter and a bit more settled in. “We choose to live here. It’s wonderful. This is a great little town!” But that New Jersey thing – “in the shadow of the city” – it’s so devastating. It’s very emotional and it creates a deep melancholy, but also a hope. It’s literally who I am.

You’ve cited a nostalgia for John Hughes’ movies, what they stand for in your mind, and how they’ve affected your songwriting and production style. How has this pervading sense of ‘80s nostalgia informed your music?

The ‘80s were a complicated period. Most periods are. What speaks to me about the ‘80s was the willingness to accept dark feelings in some big songs. There was more rage in the ‘90s, which was when I grew up. The music in the ‘80s was so goddamn pouty. It’s such a relatable vibe. My biggest influence is more ‘70s, like [the band] Suicide – that’s sonically what touches me the most. But there are certain sounds – such as the low end on a [Roland] Juno 6 that is just heartbreaking to me. Some of the string sounds on a [Yamaha] DX7 are so bizarre and warped; they send me into an emotional tailspin. I feel like I had a bigger connection to it a decade ago than I do now. I’ve been really into mixing lately. I’ve been obsessed with putting acoustic 12-strings on top of the low end coming from a Juno synth. You grab sounds from different decades. I love the way snare drums were treated in the ‘70s. I love the way bells of all kinds were treated in the ‘60s. They were so reverbed, and the pitchy tail would carry on forever – like the [Phil] Spector recordings. I love the low end of the ‘80s [more] than that of modern times. It was more interesting. It’s become very commonplace [today] to make your low end follow very specific melodies. The low end in the ‘80s had weird stuff going on. I love the looseness of the ‘90s. I like ‘90s style guitars. I’m pulling from all these different places. There are certain sounds you hit. Put a certain reverb on the snare drum, or the higher registers on [Oberheim] OB-8s and Junos is unmistakably ‘80s. I don’t store patches, ever, and I won’t use soft synths, not even to mess around. If I know I can pull up the exact same sound [a second time], part of me dies. If I can pull it up, then anyone can pull it up! What I dislike about a lot of modern recordings is that the pitch is so goddamn perfect. I mess with Auto-Tune all the time, and I love plug-ins and messing around, but it’s got to start with something [unique]. I don’t want a soft synth and then plug-ins, because then I have a chain that, while unlikely, is technically recreate-able. Anyone who knows the Moog [Model D] – what’s the first thing you do after you tune it? You tilt the oscillators a little off. That’s what sounds great. I can hear in my recordings when we’re on month three of that piano not being tuned. All these create a human sound. It’s what people love about music. And it’s got nothing to do with genre. The greatest pop music in the world has these wavering tones. If you think about Prince, sounds are wavering in and out. They’re phasing, they’re imperfect. Everything here is always one click away from going through the Binson [Echorec tape delay] or the [Roland] Chorus Echo. I’m recording the room – anything to create a situation. Which is a pain in the ass. Sometimes we shoot ourselves in the foot where “that’s the vocal tone, and it’s not coming back,” because it’s those mics going through the Binson at who knows what setting. What are the odds the tape will ever spin that exact same way again? It’s cool. That’s what you’re looking for – those moments.

Near the top of your list of ‘80s influences is Yaz and Depeche Mode. What was it like to work with Vince Clarke as one of your producers on the Bleachers album Strange Desire in 2014? You did everything over email.

I spoke to him yesterday, actually. We spend time together, but we’ve never worked in the same room. It’s just a vibe I got from him. He has this cave of a studio [in the basement of his home in Brooklyn]. You go down and he’s got a museum of synthesizers. A big part of producing records is figuring out how you’re going to get the best from someone. I don’t need Vince’s name on my record. Believe me, it’s cool, but what I need is for Vince to have a good time. I’ve given him songs, and then he’ll send me back more tracks. Anytime you work with anyone who’s specifically affected your sonic DNA, it’s weird. You hear them doing parts that you have very specifically lifted and done again, and then given back to them, so now it’s this crazy loop. I learned how to play synthesizers because of Depeche Mode and Yaz. That’s why I love synthesizers, which, in my opinion, is a very good jumping off place. Synthesizers are so delicate. You’re tweaking and tweaking until you finally hear that perfect sound. To send Vince my Bleachers tracks, which are so influenced by him, and having him play on top of a sound that he, in some way, already did – through me – it’s weird. But that was a lucky relationship to have. He’s the Picasso of synth.

You were showing us samples of glass being broken before we started this interview. You’re a collector of sounds and samples that you’ve recorded yourself at various locations over the years.

If I hear something that I feel like I’ve never heard before, I get new ideas. All that matters is what inspires you. I know what inspires me. I always want to be out there – a little scared, a little concerned, because I’m in new territory. If I’m not, some version of artistic depression would set in, because I’m somewhere I’ve been before. I always want to be looking around and sifting through places I don’t know. The only way to do that is to keep confusing myself. I don’t write on the Juno anymore. I love it, but some of the tones bring me to a place I’ve already been. That will change. I had that with the guitar for a while, and now I’m back on it. There was a period when I could not stop running everything through the Binson. I’m off that right now. Anything that freaks me out and shocks me. It’s almost like the most basic concept of a lot of psychotherapy or treatment: shock the person into a new place.

Do you put forth conscious daily, or weekly, efforts to make big changes, to force growth?

I make big efforts to take myself out of myself, but I also have developed good armor for when I know it’s right. If you get “there” and don’t know you’re “there,” that’s a big problem. Defining that you’re “there” is a feeling. You need to have style and feeling, but you can learn [the technology]. It’s pretty easy to know what gear is great and how to patch it all together. You can go nuts making interesting sounds. There’s a lot of finesse there, but it’s learnable. To know that you have “it” and you’ve hit “it” – by the way, it’s not like 90 percent, or you’re “almost there,” or you “pretty much have it.” You do it, or you don’t. You have the recording, and you have the song, and you have the takes, and you have everything in the mix – or you don’t. To know when you’ve hit that feeling, that is the most important skill.

I’ve heard you talk about this notion that, in the end, all that matters is the mix and what works. This speaks to what evokes the most authentic version of the feeling you’re trying to capture.

That’s 100 percent true. So many records have been destroyed by people getting obsessed with, “But we spent a month on that string section.” But it doesn’t sound good. “But remember when we stayed up all night and we pitched these bells together until they were perfect?” But they don’t sound good. You’ve gotta be okay with that.

And if it doesn’t sound good, if it doesn’t serve the song, are you a strong believer in scrapping it?

To do this work, you have to be acutely aware of the fact that you might work on something for a month – whether it’s recording it, writing it, or mixing it – and then walk in one day, throw up a mic, and do it better [in that moment] than that whole month. If you can’t come to peace with that and realize that that month was just a part of you getting there, you’ll go crazy.

Does this translate into your mixing process as well? Do you tend to favor a subtractive mixing strategy?

I do that more in the production phase; I’m always mixing as I’m going, because it informs every decision. It’s unfair to a song to not have it sound right along the way. The way I treat mixing is, if I mix a record, then it’s because I have it there, and I need to make it gel. If I send a record to mix, I usually work with Tom Elmhirst or Serban Ghenea. I either want it a little bit pushed over that hill, or I’m interested in having someone tear it apart. During the production phase, there’s a lot of, “All right, take everything out, and let’s hear the vocal and the bass.” I feel like my process is commonly like: I do things, do things, do things – and then take it all out. Sometimes you have this big mess that feels so cool, and sometimes I’m like, “I don’t know how we got here, but this is awesome.” You learn. Different albums are filling in puzzle pieces. In the beginning phase [of recording] this Lana Del Rey album [Norman Fucking Rockwell!], we were messing around. There are pianos, and acoustics, and a drum set. We were also throwing 808s on; totally messing around. When we recorded a song called “Mariners Apartment Complex,” we said, “Oh, there it is!” It’s this drum sound, where it’s very roomy but quiet. I turned off everything but the overheads and the room. It was this quiet drum take, but there was so much room in it that it was amazing. “That’s the drum sound for the album!” Then there was a very specific piano which happened to be in Conway Room C, recorded a very specific way because we had eight mics on the piano. The close mics sounded weird, and it was a specific vocal tone. I start to fill in this palette, and once I have the palette, then I have tools. “Now let’s attack all the songs through this palette and see if it’s going to keep working.” If it does keep working, then you might have an album.

In the case of that Lana Del Rey project, it sounds like you decided to go organic across the scope of the whole album.

That album’s totally organic. We talked about the theme of an album – or maybe there is no theme. When you’re making an album, there’s a period of time where you’re totally messing around and want to be in rooms like this where you touch a whole bunch of instruments and see what happens. Once the people in that room have a glimmer of what that palette is, then you can start seeing if it’s going to be something that is exciting for an album. Sometimes you’ll land on a palette. You’re recording, and a month later you say, “This doesn’t really do it for an album.”

Let’s talk about the design and setup of your home studio. You were working with Jeff Bhasker [Tape Op #130] and fun. at NYC’s Jungle City Studios [#89]. You were so impressed with the setup there that you decided to hire the Walters-Storyk Group to design this room?

I love John Storyk – he’s a genius! He built Electric Lady Studios. He gets it. He and I are building another one in L.A. right now. It’s turning into an interesting place.

Is it around the same size and scope as this?

Much bigger. It’s an honor to work with him. I’ll say to him, “Here’s what I’m thinking…” Then he’ll come back and have an even better idea of what I was thinking! We’ve been going back and forth over email about the B Room in L.A.

What are the particular items in this room that help shape your sound, your production style, and workflow?

I don’t have a Fairchild [limiter] here. I’ve been recording a lot of drums, so that would be a goal. These [Chandler Limited] EMI strips – the TG2 rack units – the lack of options makes me way more creative. I used to be obsessed with recording amps. I don’t think I’ve recorded a guitar amp in a few years because of these strips; I’ve been doing all my guitars and basses [through] them. If I have a distorted tone, it’s that. You have your red and blue-gray knobs, and you’re in this dance of how much you’re going to distort it. It’s so dynamic and reactive to my playing. That’s my favorite way to get these tight, incredibly gritty sounds. I’m extremely obsessed with tape delays. At Electric Lady, I’ve got a bunch of other ones. I just got a Binson [Echorec] Baby. It sounds totally different from the full-sized one I have here. I love this German one, the Echolette NG51 from the ‘60s. I’ve had it for a couple of months now at Electric Lady, and I put it on everything. The ‘70s Watkins Copicat is my favorite piece of gear right now at Electric Lady. What I love about it is the tape is right there, so when I’m recording something on tape, I’m messing with the swell with one hand and literally squeezing the tape with the other to manually slow it down. The Copicat has four knobs, and you don’t see anything – just the tape sitting there. It’s not covered by anything. It’s fun to put your hands on the tape. I’m doing it to an absurd [degree], feeding it back and then squeezing it. Physically manipulating tape and tape echos on drums and vocals. I’ll send them into the EMIs and blow them out that way. I don’t feel like I’m hearing a lot of that. It really excites me.

Let’s talk about your collaboration with your longtime engineer, Laura Sisk.

She’s at Burning Man right now. Please print that!

Is Laura’s role more as a tracking engineer, or does she also share in the mixing duties?

Mixing too. We basically do everything together. I believe in keeping the room as small as possible. Anytime we work, it’s me and her, or me and her and anyone we’re working with. I don’t like having a lot of people around. You could be working on the biggest album in the world – you don’t need a big staff. You never need more than one other person in the studio – besides maybe if it’s a big studio and you’re recording a big session with assistants. We do everything together – there’s a sonic language that’s so quick. She’s a brilliant tracking engineer, and a brilliant mixer. Unbelievable vocal producer. A lot of times, editing can be the difference between making something usable and making something shit. I’ll go in, play drums, and say, “Okay, I want the bridge and the chorus.” Then she edits it and it sounds how I want it to, which is not perfect. I don’t want it on a grid. I want it a little bit more presentable than what I did, but I want it to sound like me. I only work with her now. But in other experiences I’ve had, that “little bit too much” ruins everything and makes you want to go home for the day.

How did your collaboration start, and how long have you been working together?

She was engineering for a producer named John Hill, who I was doing the first Bleachers album [Strange Desire] with. We did that whole record, the three of us. Then I was starting to make other records and seeing if she wanted to come help. It’s six years later at this point, and we pretty much work together every day. It’s such a delicate thing to be able to pick up on peoples’ cues. Every time you put a body in the room, it’s a plus or minus, and she’s always a plus. She always brings more to the picture. She’s got a great ear for everything. We have similar goals, and the bar is constantly being pushed. To work with people where, when something happens, no one says, “It’s good enough.” That’s what people deserve, if you’re going to put this music out into the world. Gear is way secondary to developing the skill of being able to capture something exciting, different, and honest. You can do that on the crappiest rig on earth. My advice to people is to focus on capturing a vibe. Don’t try to make your records sound like other people’s records. It’s already been done. If you’ve got Pro Tools, go nuts in there. See what happens. The ultimate goal is to do what you feel truly sounds like YOU – and then to feel proud to share your work because you’ve hit that level on all fronts: the production, writing, mixing, and everything.

Check Jack Antonoff Instagram Account

Bren Davies is a singer, writer, and voice coach living and working in Brooklyn, NY.

Brian T. Silak is a professional freelance photographer from New York City. His work focuses on creative personality portraiture and graphic illustration.