“I don’t know if I would have been a decent architect,” the film composer Carter Burwell recently mused, sitting in the private studio attached to his house on the Atlantic Ocean, east of Amagansett. “But my interests — design and engineering, art, math — all come together in architecture, so it seemed like a logical progression.”

Instead, the composer of scores for a long list of critically acclaimed films by the Coen Brothers among many others, and more recently “The Morning Show” on Apple TV+, postponed architectural study for the musician’s life in Manhattan, where he performed and recorded with bands including the Same and Thick Pigeon. “It wasn’t a difficult decision,” he said of the planned one-year deferral. “Of course, if I look back now, I see that same set of interests are all present in what I do now as well, adding my interest in film.” Composing for film, he said, “manages to touch most of the parts of my brain that I enjoy being massaged.”

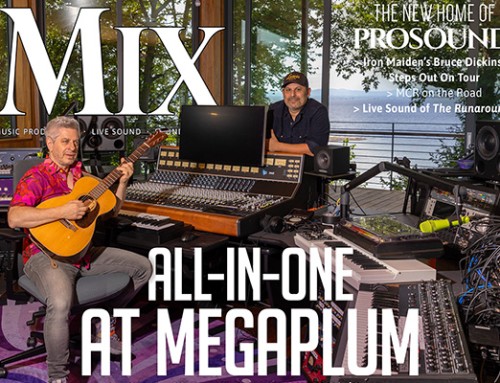

The house in which he lives with his wife, the artist Christine Sciulli, and their three children was recently renovated, and the sunlit, state-of-the-art studio completed. On a recent afternoon, as waves silently crashed onto the sand through a window framed by the left and right speakers of a surround-sound speaker array, Mr. Burwell reflected on inspiration, technology, the vagaries of the entertainment industry, and becoming, or not becoming, a local.

Like parallel walls, glass introduces unwanted sonic reflections in an acoustic space, but Mr. Burwell insisted on views of the ocean and, behind the digital audio workstation that looks out to it, the pines of Napeague. “Being able to look out at infinity is so important psychologically, and good for my eyes, too,” he said. John Storyk, who a half-century ago designed Electric Lady Studios for Jimi Hendrix, knew of Mr. Burwell’s affinity for natural light, having designed his Manhattan studio 20 years ago. “That turned out very well,” Mr. Burwell said. “When it came time to do this, I didn’t have any question that John would be the guy I would go to. I had him come out and take a look at the site and see that the views are really important. You don’t normally walk into a studio and see floor-to-ceiling panes of glass looking out at pine trees and the ocean, but it’s, I think, by far the most important feature.”

That unusual element, like the eccentric, sometimes subversive Coen Brothers films he has scored — “Fargo,” “Miller’s Crossing,” “The Big Lebowski,” and “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs” among them — aligns with Mr. Burwell’s atypical career path. “When I started doing this, it was more common that people came from a conservatory background,” he said. “I come from a technology background, I didn’t study music in school.”

He was not entirely alone. “At the time I was entering, there were a few other people coming from a similar background. Hans Zimmer was a synth guy and a tech guy, and Danny Elfman was coming in from rock ’n’ roll. The whole body of people doing film

scores was beginning to change right then. There were more of us from less traditional backgrounds.”

As it happened, his foray into composing for film also coincided with a growing digitization of recording. “The technology allowed me to get into this,” he said. “Right when I began doing film scores was when the first bits of software for composing on a Mac computer were coming out. I started using it right then, and I still use it today, but of course it’s evolved enormously.”

Technology influences more than content creation, of course. Digital recording and the internet upended a long-established music business model in the 1990s and beyond, and the film business would soon be similarly impacted, particularly on the distribution end. “Streaming is clearly the future, everybody can see it,” Mr. Burwell said. “Some are scared about it, some are excited about it, but it’s clearly the future. There’s so much money being thrown into generating libraries for all of these services that it’s a little bit of a ‘Wild West’ thing. Netflix is opening up its pocketbook to make as much as it can to beat its competitors.”

Fortunately, he said, that largesse may allow an upcoming Netflix production for which he is in discussions to include an orchestral score as opposed to the “virtual orchestras” enabled by digital media. “Which is great,” said Mr. Burwell, who works within a wide range of budgetary allowances, “but also puts a certain pressure on me to write and orchestrate and record orchestral music in basically a one-episode-a-week schedule. I might be in a totally different emotional state a couple of months from now, but right now I’m excited by it.”

But first comes its conception. What is the creative spark, and where does it come from? “Just as I did when I was in my teens, I play the piano every day, improvisationally — I don’t play written music at the piano,” he said. “My only interest is making things up; I don’t have to have a project. And when I come up with something that I like at the piano, I try to record it on my phone or write it in a little book.”

Composing for film is another question, he said. Some scores complement the visual element — think action movies, tension building to spectacular explosions, for example. Mr. Burwell prefers a different approach. “Most of the time the film has been shot and roughly edited, so usually my approach — it’s easy to say, not so easy to do — is to watch the film and think of what is missing. I think, just for myself as a viewer, what could music add to the film that isn’t there already? And that’s entirely personal. Another person would look at it and have a completely different answer.”

Like the filmmaker, for example, “but even in those cases, I can sometimes get them to see it my way,” Mr. Burwell said. The Coen Brothers have not always agreed with his creative decisions, “but that’s the important thing in our relationship: They also don’t dismiss things out of hand. I think that’s one of the reasons we’ve managed to work together for so long, is that they will usually give me some rope to try out an idea. And if they still don’t get it a week later, we’ll move on. And sometimes they don’t have anything in mind,” one example being “Fargo.” “Those are sometimes the most fun for me. I really just free-associate and try to find a solution.”

Much of film scoring is problem solving, he said. “It’s saying, what is the problem of this film? And once I figure out that problem, what would be a good musical solution to it? Of course, it doesn’t answer ‘Where does a melody come from?’ That’s a whole other mystery.”

Mr. Burwell and his family have been year-round residents for 10 years. “I had never spent a summer here until we moved here and bought the house,” he said. “We jumped in with both feet, we just committed. I have to say, we were kind of stunned when we saw what Amagansett is like in the summer.” The composer allowed that year-round residency makes him something of an anomaly among the South Fork’s many entertainment-industry professionals.

For five of these 10 years, he has served on the Amagansett Fire Department. “This totally overstates it,” he said, “but I wanted to choose sides. I wanted to be part of the community, and that seemed like a good way to do it, because I knew that they really needed people.”

“I wanted,” he continued, “to somehow plant my flag in the sand and say, ‘I’m a full-timer.’ I don’t want to be viewed as a summer person or a visitor. I say this,” he added, “knowing that I could be here until I turn 100 and there will be people who still view me as a newcomer.”

Photography by Tycho Burwell