With Help From Herb Alpert, Letting the Light In at the Harlem School of the Arts

Dorothy Maynor never sang at the Met, but the school she founded is glowing anew, thanks to the revitalization of its beloved “gathering place.”

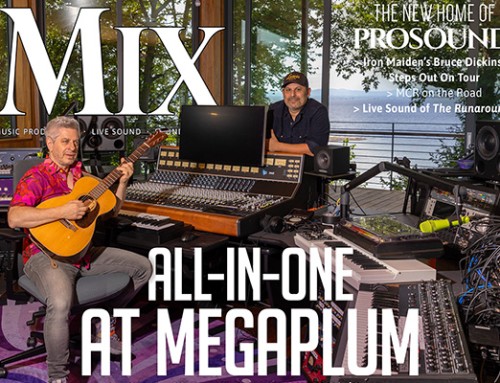

Renovations were completed last month at the “Gathering Place” of the Harlem School of the Arts, now named for its founder, Dorothy Maynor. Credit: Elias Williams for The New York Times

By James S. Russell

A typical Saturday at the Harlem School of the Arts would find families chatting with each other as one child runs out of a dance class in tights, or another lugs a viola. A quick bite or check-in with parents, and they would dash to a drawing or singing class.

This happy noise occurred in what the school’s founder, Dorothy Maynor, called the Gathering Place, a two-story-high room that also hosted performances and exhibitions of student work, and where performers from the worlds of jazz, Broadway and classical music would drop by so that children could see and meet working artists up close.

But the Gathering Place, which dates from 1977, was enclosed by concrete-block walls. Children and families came in through a forbidding brick entrance.

New entranceway to the school, on St. Nicholas Avenue near 141st Street. Credit: Elias Williams for The New York Times

Today, the school has completed a thorough transformation inspired by an architect Celia Imrey, and a major patron: Herb Alpert, the trumpeter and record company executive, whose foundation has contributed a total of $17 million to the school, including $9.7 million for the recent upgrade. A glass facade floods the space with morning sunlight, ready to unveil the students’ beehive of activity at the school, on St. Nicholas Avenue near 141st Street. An upper-level corridor doubles as a wood-paneled balcony, reached by a grand switchback staircase. The space has been equipped with sophisticated acoustics, and advanced theater lighting and sound.

“I mourn the level of energy this place had,” Eric Pryor, the school’s president, said, looking forward to the school’s post-pandemic future, when children and families can return. (Many students continue to take classes by video.)

With many performers and arts organizations staring at a financial abyss, the Harlem School of the Arts has risen and thrived through adversity.

Eric Pryor, president of the Harlem School of the Arts, in the Dorothy Maynor Hall. Credit: Elias Williams for The New York Times

Ms. Maynor was an acclaimed lyric soprano of Black and Native American ancestry with a wide smile and a talent now largely overlooked. “Miss Maynor’s voice is phenomenal for its range, character, and varied resources,” wrote The Times critic Olin Downes in a review of a famed concert at Town Hall in 1939. She sang classical repertory at the world’s concert halls, but retired in 1963, having performed at Dwight Eisenhower’s presidential inauguration but never at the Metropolitan Opera, which did not hire African-American singers for leading roles when she was in her prime. (She died at age 85 in 1996.)

The Harlem School of the Arts, which offers classes in music, dance, theater and visual arts, was Ms. Maynor’s second act. She sought to serve children who had no exposure to arts in public schools and no access to private instruction. She would say that children were made to believe that beauty did not exist in their community but only beyond it.

Dorothy Maynor, the school’s original founder, with some of the children who attended the school, which she started in the community house of St. James Presbyterian Church. Credit: via Harlem School of the Arts Archives

She started the school in the community house of St. James Presbyterian Church, where her husband, the Rev. Shelby Rooks, was rector. The classes promptly drew swarms of applicants even as Harlem was wracked by protests and riots in 1964 after the fatal shooting of a Black teenager, James Powell, by a white off-duty police officer.

The school finally moved into its own building next to the church in 1977. Its architect, Ulrich Franzen, designed the school around the Gathering Place, as Ms. Maynor had requested, to more generously accommodate parents who had spontaneously appropriated a hallway in the community house to savor their children’s development.

With New York City just two years past its brush with bankruptcy, the new 37,000-square-foot building with studios, practice rooms and four large dance spaces designed with the help of George Balanchine, was an extraordinary act of faith at a time when the city’s future was very much in doubt.

Though the school thrived for years, it was forced to close its doors in 2010 because of poor financial management. Kate Levin, commissioner of the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs in the Bloomberg administration, coordinated support to get the school back on its feet.

Herb Alpert, the trumpeter and record company executive whose foundation has contributed a total of $17 million to the school. Credit: Michelle V. Agins/The New York Times

A donor appeared unexpectedly from California as if conjured by Ms. Maynor, who had been a prodigious fund-raiser: Herb Alpert had read about the fate of the school. “It had given such creativity to the community,” he recalled by phone from his home in Malibu. “How could people in New York allow it to fold?”

He matched the funds Ms. Levin raised from several donors: $500,000 from his Herb Alpert Foundation founded with his wife, the singer Lani Hall. In 2012, when new leadership was in place and the school was again humming, Mr. Alpert added $2 million to erase the school’s debt and established a $3 million endowment for student financial aid.

“Herb sticks out as an unusual cat on the philanthropy scene,” said David Callahan, the founder and editor of Inside Philanthropy, a website that monitors givers and their gifts. Few philanthropists rescue foundering organizations or retire debt, he said. “They want to set sail with the ship, not go down with it.” He added, “Arts education is a big gap in the philanthropic marketplace.”

Mr. Alpert’s fortune derives substantially from the sale of A&M Records in 1989 for $500 million. The foundation mainly supports arts and music education. The Harlem School is one of Mr. Alpert and Ms. Hall’s legacy organizations, which receive sustaining gifts over time.

Mr. Alpert said the trumpet he picked up in grammar school “had taken me so many places in my life. I think every kid should have that opportunity at an early age.” Rona Sebastian, the foundation’s president, added, “Getting rid of the debt was the only way to save the school and work toward the future.”

In 2017, the unrenovated facade of the Harlem School of the Arts, with a solid front wall that did not clearly transmit the school’s mission. A 70-foot-wide metal and glass expanse has replaced it. Credit: Andrea Mohin/The New York Times

When Mr. Pryor asked the architect, Ms. Imrey, to look at some problems with the building in 2018, he inquired about how the school could more clearly transmit its mission to the community. “I said they should get rid of the solid front wall,” Ms. Imrey explained. She sketched a 70-foot-wide metal and glass expanse to replace it.

“I insisted on this huge glass front door,” Ms. Imrey said. “I had this image of a young girl running to her lesson from the subway. She would run up to this big door but be able to open it herself. This makes the school her place.”

Mr. Pryor liked “taking the veil off the front so people could see what was going on.” And Mr. Alpert agreed to support the renovation. “When you feel good and feel welcomed, you bring creative energy to a space,” he said. “That’s what we wanted to create.” What’s now called the Renaissance Project was born.

Mr. Alpert brought in the acoustician John Storyk, who had worked on Jazz at Lincoln Center. Mr. Storyk proposed sloping the glass wall outward to reflect the sound around the room. Arrays of speakers permit multiple seating and performance configurations. The advanced theater technology is expected to attract more talent to the school and, ultimately, lead to income from outside events.

Looking out from Dorothy Maynor Hall to St. Nicholas Avenue. Credit: Elias Williams for The New York Times

With the completion of the Renaissance Project last month, the facility has been renamed the Harlem School of the Arts at the Herb Alpert Center. All the new possibilities await a time when the school’s programs for adults and children can resume.

“We’re looking at forming small pods of kids, especially for dance,” Mr. Pryor said, noting that practicing at home doesn’t work: “You can’t move properly in a kitchen” As the school moves urgently though cautiously toward reopening, he pointed out, “Some kids and their families are dealing with depression, separation anxiety, loss of family members, isolation. A few are homeless.” He imagined having them all back in the Gathering Place, now officially called Dorothy Maynor Hall, after their first patron.

“I know,” he added, “that they would eat this up.”