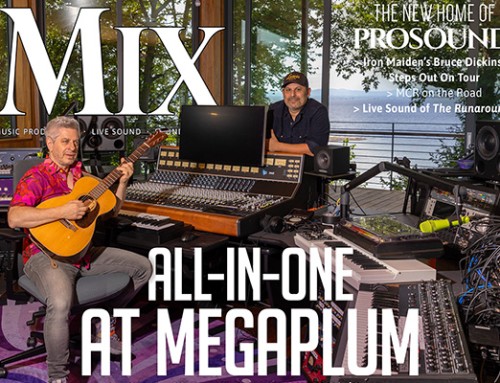

Interview by Matthew Fellows

The industry stands at a crossroads as we make the leap into a new generation of studios. April saw the demolition of the original ‘U2 Studio’, Windmill Lane Studios in Dublin, just one of a dwindling number of places that stood to represent the golden era of recording.

But although the old premises has now gone, we investigated and found the studio still trades today in a new facility, going from strength to strength.

New York’s Electric Lady Studios (ELS) – famous as the brainchild of Jimi Hendrix and Eddie Kramer – is among the few that have resisted the effects of time and stayed successful and relevant into its 45th year. So why have studios such as ELS succeeded in sticking around while others have folded? Perhaps studios aren’t meant to last forever?

Who better to ask than the architect of both? We caught up with studio designer John Storyk (main picture) to get his views on the longevity of studios, and the secrets that make it happen.

“I teach at Berklee [College of Music, Massachusetts] – and I was going through some slides of studios, and a number of them – all studios we designed – are closed!” Storyk tells us. “One of the students asked ‘Why is that?’ and I said ‘Most studios don’t stay open.’ And I don’t think that’s a problem. Technology changes – studios are often a business, but more often they are a passion, and sometimes the passions change.”

With a career spanning 45 years in the industry, Storyk has been around to witness more than a few paradigm shifts, but recent times may have brought about the most drastic alterations, and it’s becoming ever more difficult for establishments of a fading era to keep up.

“Certainly in the last 15 years, business models in our industry have…’changed’ wouldn’t be the right word at all,” he continues. “It’s going through a revolution. So as a result, everything associated with it, from studios to equipment to distribution chains, is completely upside down. So it doesn’t surprise me that studios change.”

Secrets of Success

So what are the key elements that enable studios to outrun their age?

“The ones that survive, I think each one has it’s own special story,” Storyk explains, “and it’s probably rooted in some combination of quasi-intentional and quasi-accidental facility, a stroke of luck or genius along with a lineage of passion for delivering great service. If you made a survey of studios that are 40 years old and over – which, by the way, would be a very small survey – I think you’re going to see this combination: some good bones, in some instances accidental, then you’re going to see an ownership chain that continues to inject passion as far as keeping up technology and delivering service.

“That’s another thing: most studios that last a long time, they have a signature of some sort. It could be an acoustic signature, it could be a style signature, it could be a service signature. There’s some sort of signature that allows people to feel very comfortable when they walk in the door. When you see all of these things line up, I think you see studios staying alive a long time. Even when you have them all, sometimes they still close. Because I think they’re meant to close.”

Electric Lady has carved out a legendary name in recording history, and given its origins, it seems it was always destined for greatness. But it hasn’t always been a smooth or premeditated journey.

“It didn’t even start off as a studio; the project started off as a club,“ Storyk recalls. “I met Jimi and Eddie Kramer, who was more of an inspiration on the studio than Jimi himself, and then when it shifted from club to studio, they allowed me to stay on the project. It originally was the lower floor of a small two-storey building. The building was built in the twenties; it was built to house the film guild of New York City, and the main floor had a movie theatre up until the nineties, on top of Electric Lady. The studio itself was built in the basement in what was a club, a blues club called The Village Barn. They bought the lease to the club, they didn’t buy the building; to this day they still don’t own the building, they pay rent on it.”

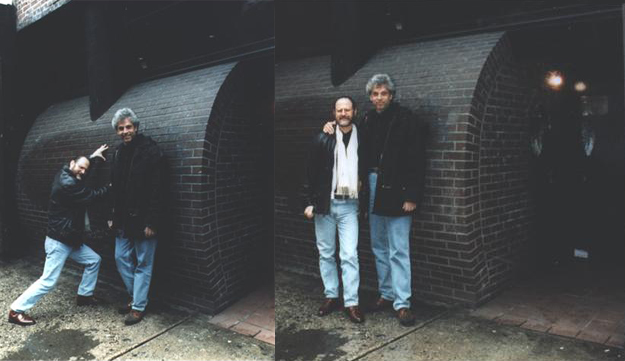

Pictured: Storyk with Eddie Kramer outside Electric Lady in 2000, 30 years after its construction. The curved entryway was later demolished by the building’s owner.

Throughout the studio’s long history it has proven to be no exception to Storyk’s golden rules. It owes much to good old-fashioned luck, and even more to some skillful guidance throught the years.

“In the case of ELS, it was quite a lot of good fortune and getting some good bones for the place,” he continues, “along with now an extraordinary manager, Lee Foster. Because basically that studio was down for the count; it was about one minute away from closing. He almost single-handedly brought it back to life. It was at the eleventh hour when it was sold to a new owner, and he kept it alive, he did not allow it to be sold or to be taken apart, which is probably what would have happened. And now it’s flourishing under Lee’s leadership; he’s taken it and expanded the building as much as it could be, because it’s actually somewhat limited, and they’ve gone in other directions like managing and property rights. Under Lee’s vision, he’s brought it into a new era.”

And of course, beyond these key factors, a huge contributing factor to its longevity has been the studio’s original layout and sturdy construction; an approach that is seldom found in the industry today.

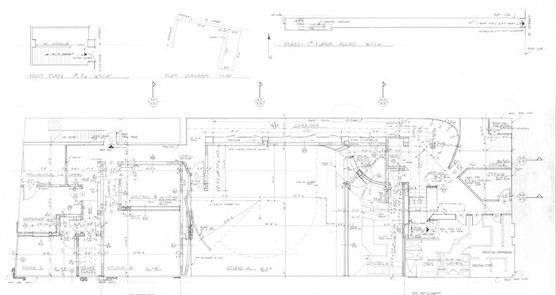

Pictured: Storyk’s original hand-drawn diagrams of ELS’ basement floor plan.

“The main studios were downstairs, an A room and a B room, and they’re still basically there. It’s been modified a few times over the years; the control room got pushed out, the monitoring changed, the console changed, but Studio A live room is essentially unchanged. The B suite is also relatively unchanged, except the studio became a control room and the control room became a studio/lounge. Upstairs, we did a C room years later – that’s stayed unchanged but it did get modified a few years ago by Lee and he’s put in two other, smaller rooms that are production studios in the offices upstairs and they’re doing very well. The building can’t really grow anymore.”

“There’s no reason to touch Studio A, there’s something going on in that room that works. The nature of how we built studios then were much less temporary; for instance, the entire structure was built out of sand-filled masonry. Modern architecture is basically cheap architecture – that doesn’t mean it’s bad, but the lingua franca of modern architecture is thinner materials. Most buildings you see now won’t be here in a hundred years. Notre Dame will still be here in a hundred years. But Electric Lady was built to last, and I don’t think it was built to last because everybody thought it would be here in 45 years. I think it was built to last because it was just the only way we knew how to build things. Now, the nature of how we build is a little bit thinner, but also people aren’t afraid to think in terms of something not being here in in ten years.”

Pictured: Formwork for the studio’s sturdy split slab construction.

Even with such resilient construction, Storyk is dismissive to the idea that he would ever have dreamed the studio would last this long.

“No, I was 22 years old,” he replies. “I believe Electric Lady and five or ten others studios are the beginning of a golden era of studios where the artists took control. And that of course ushers in an extraordinary era of independent recording studios, even to the point of excess, but when that was happening I was 22 years old, I had no idea.”

The Flipside

But, even as the number of ‘Golden-age’ studios continues to dwindle, Storyk is both realistic and optimistic about what this means for the future of the industry:

“I love that these studios are still alive, but it doesn’t sadden me or even surprise me when one closes down – its time is over,” he notes. “Like when The Hit Factory closed in New York; it didn’t close because it was empty – it was completely full! It closed because the land was worth more money. The original owner had passed away and his wife wasn’t that interested – she took the money, and that’s OK. The flipside to this story is that every time one of these legacy studios closes, there’s 150 new ones popping up of all ilks and sizes, with sensational rooms and in strange places. I find that to be extremely exciting, I don’t find it a sad moment when a studio closes its doors, as long as we make sure we’ve got the flipside of the song.”

As for Storyk, his eyes are firmly set forward: “People always ask me: ‘What’s your favourite studio?’ And I say: ‘The one I’m working on today.’”