Let The Rhythm Be The Lead

Jackson Browne’s Personal Approach to Songwriting, Recording and Social Activism

Download the Entire Article Here (7.3 mb)

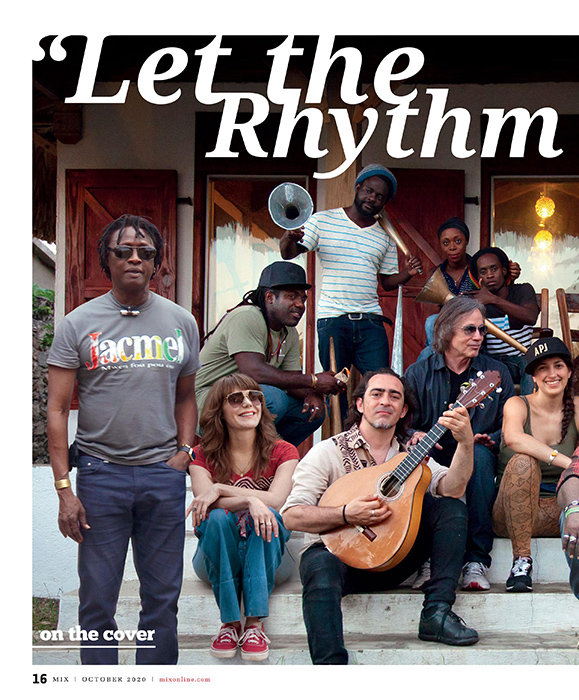

Jackson Browne smiles as he overhears one of the students in the breezeway at Haiti’s Audio Institute singing the hook of his song “Love Is Love.” “Love is love, love is love, lanmou se lanmou,” as the young man took a break where 40 students convened to learn the art of recording, all in connection with Browne’s most recent benefit project, the World Music project, Let the Rhythm Lead: Haiti Song Summit Vol. 1 Most people familiar with Jackson Browne know that he is a songwriter, recording artist, producer and activist. This project, recorded in two weeklong sessions in Haiti—united all those roles: As a songwriter, Browne contributed to a few songs, but “Love Is Love” was his (David Belle collaborated on lyrics) as writer and artist. He co-produced the record with Jonathan Wilson, and proceeds benefit Artists For Peace and Justice in support of the Academy for Peace and Justice and the Artists Institute of Jacmel, Haiti. Browne grew up in the 1960s, first in the Highland Park area of Los Angeles, which he describes as predominantly Mexican-American, with a certain amount of racial tension. He credits both his parents—in different ways—for his social consciousness. His dad, a musician, loved jazz and Dixieland and introduced him to all kinds of Black music, and took him to see Lightnin’ Hopkins sing at the Ash Grove, L.A.’s roots music folk club. He was the one who sat his son down to have that important conversation about prejudice, as racism was referred to in those days. His mother protested the Vietnam War. Then, while living in Orange County as a teenager and encountering real class divisions for the first time, his older sister Berbie went to San Francisco to demonstrate at the Republican convention against Presidential candidate Barry Goldwater in 1964. By the next year, he was visiting his sister at her apartment in San Francisco, experiencing peace and love in the renowned Haight-Ashbury district, listening to the Staples Singers and jazz organist Jimmy Smith.

THE RECORDING ARTIST

By 1967 Browne became a fan of bluegrass music, and also joined the newly formed Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, which at the time was a traditional jug band; Browne played guitar, washtub bass and jug. After a few months, though, Browne realized that he had to depart to concentrate on his own songs. When he began making records, he worked with producer-engineers or co-produced with engineers. After his third album, co-produced with Grammy Award-winner Al Schmitt, he began producing, beginning with Warren Zevon’s debut and its follow-up, Excitable Boy, co-produced with Waddy Wachtel. He made in his house, and finally Groove Masters in 1986 in Santa Monica. He says he bought a Neotek console because Ladanyi advised him that it was the lowest-costing, still-possible-to-maintain, board available. “But it didn’t sound as good as what I eventually wound up with, which was a Neve, but that was quite a few years later,” Browne says of his 8078 that David Manley found for him. He says that even though he can’t talk about the equipment technically, he knows how it sounds. “I still don’t know how anything works,” Browne admits. “The engineer and I have a dialog, which turns out to be the best way for me to get what I want out of the studio. The engineers I work with have become more and more like a confidant to me. I explain why I want to do what I want to do, and they are there to facilitate that.”

THE ARTIST-ENGINEER CONNECTION

Singer/songwriter/producer and studio owner Jonathan Wilson, who has known Browne for those two albums and two of his own, back to back, in four years. Browne figured that he needed a studio. Well, it was more like his business manager figured that out. He told him: “You spend so much time in the studio and it costs you this much an hour, you might want to think about having your own studio. It would end up saving you a lot of money, even though it would be a big cash outlay.” He also said to him: “And look at you, you traded in your job as an artist for a job as producer. Congratulations! You’ve just taken a 90 percent pay cut. But if you worked in your own studio, at least you’d be making some money on that end.” By that time Browne was working with Grammy Award-winning engineer Greg Ladanyi, who helped him get a studio up and running. The first things he bought were a Studer A80 and a Neotek console. His first studio space was in a warehouse in Downtown L.A. in 1982, then nearly a decade and accompanied him to Haiti to work on the recent project, indicates that Browne knows more than he lets on.

“He’s built himself an amazing, first-class studio that he sits in every day,” Wilson says.

“’Does he bother himself with all the model numbers?’ No. But Greg Ladanyi was sort of his guru, and Ladanyi told him a lot of great stuff to get, and when you get into the habit of sitting with an engineer, you know what it does. And he certainly knows when something doesn’t sound right.” Most artists who have studios don’t book them out, but to defray some of the costs, Browne does, and the benefit is that he learns from the other artists recording there. While Browne says he doesn’t “haunt” the studio and hang around while others are working in it, he talks to his engineers and takes note of how they are working. “It’s like having a master class, only they don’t know they’re giving it,” Browne laughs. ”I don’t ever touch anything, but I may come in late at night and see where they put the drums. Some people do some crazy stuff. David Briggs had this band in there that was set up in a circle. The singer was in the center of the room, with no separation, and everyone was set up around him.”

Browne says sometimes a song may not become what he originally thought it would be. He also says that sometimes the studio dictates the direction of a song; until the musicians have at it, he doesn’t quite know what it will sound like. “You have to find out from the players what the song really wants. Sometimes I’ve found out that I wrote too many verses; it really annoys me to have to throw shit out,” Browne groans, “You mean, I have to throw that verse away because I can’t say all that before I get to the chorus?” I do a lot of editing, which is why all these workstations with Pro Tools have been so welcome to me—not because of how they sound, but for what they let you do.”

MORE THAN MAKING A RECORD

Jackson Browne’s involvement with Haiti began right after the country’s devastating 7.0 earthquake in 2010, when he teamed with APJ and a roster of musicians, film makers and actors to pledge long-term financial support to build the Academy for Peace and Justice in Port au Prince, serving middle and high school students from one of the poorest neighborhoods in the Western Hemisphere. In 2015, he went to Haiti to take a look at the school to which he had contributed, at one point spotting a tile with his name on it outside one of the classrooms. “There’s a buoyancy and optimism to everything that APJ does,” Browne says. “They got a school up and running within a year, and at this point, 10 years later, 2,600 kids go to that school for free.” During that trip, Browne visited the APJ’s Artists Institute, established by filmmaker David Belle, comprising the Cine Institute and the Audio Institute, up the coast in Jacmel. One night on the beach, musician and songwriter Jonathan Russell, who was also on that Haiti trip, became entranced in a jam with Haitian musicians and then later couldn’t remember what he had been singing. He and Browne had to get David Belle to show them the footage of that jam that Belle had filmed so they could learn it. If Belle hadn’t filmed it, it would never have become a song. That song, “I Found Out,” was the initial inspiration for the whole project. When Browne visited the Audio Institute studio, he heard a band recording on what APJ touted in their brochure as their state-of-the-art SSL console, Genelec monitors and Pro Tools rig, in a studio designed by John Storyk of the Walters-Storyk Design Group. But to Browne’s mind, they were missing much of the important analog gear that could make a real difference in their recordings. “I thought in the back of my mind, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if somebody came down here and made a record and brought some of the old gear and showed them what that’s about?’” he recalls.

It wasn’t long before that thought went from the back of his mind to the front. Still, Browne says, it took engineer Jonathan Wilson, game for the adventure, to make it happen. It took about a year before they could put it together. Of Wilson, Browne explains that they are friends and both have studios, but that Wilson “knows how to work his and I just own mine. Again, I don’t easily focus on the technical stuff. I know how things work and how to use them, but not how to fix them or even how to turn them on. I do know the process of making records. Fortunately, I’ve always had the good luck of working with great engineers.” Wilson collaborated with Browne to create a package of equipment to augment what they found on the Audio Institute’s equipment list. The package included gear from Jeff Ehrenberg (Vintage King), David Jenkins (True Tone Music), Wes Dooley (AEA microphones), EveAnna Manley (Manley), Eric Stollsteimer (Caveman Vintage Music), Ross Garfield (Drum Doctors) and Dusty Wakeman (Mojave Audio). They brought a matched pair of AEA N22 mics, a pair of MA-300 Mojave mics, some older model Electro-Voice, Shure, Beyer and Telfunken mics, two Neve 1073 mic pre’s, two Pultec EQs, a pair of old reissue Electrodyne preamps, two Retro Instruments Tube Compressors, an API 500VPR 10- slot rack with power supply, a Manley VOXBOX, a JHS Colour Box V2 Preamp Pedal, Istanbul cymbals, Drum Doctors drumheads, and left it all there as a gift to the school. All of this—the gear and the musician’s travel—Browne paid for with charitable dollars, accumulated over a period of time by adding a dollar to the price of his live concert tickets. The project became so much more than teaching recording. It became a joyous cultural exchange with seven songwriters from four countries: Spain (Raúl Rodríguez), Mali (Habib Koité), Haiti (Paul Beaubrun) and the U.S. (Jonathan Russell Jenny Lewis, Wilson and Browne)—sharing musical sensibilities and diversity, while teaching about 40 post–high school students the principles of recording, all the while speaking through translators.

LEARNING BY DOING

Browne recalls after they hooked up all the equipment and the students heard the signal chain, and heard the drums, “They went, ‘Oh, we were wondering how you get that sound to happen.’

Wilson adds that some of the Western grooves were unfamiliar to the Haitians yet interesting to them; they were also enamored of the drum kit, as they mostly employ hand drums in their music. “I could tell that seeing someone play a drum kit was a point of interest,” says Wilson, who played drums on all the songs. The night before the first recording session, everybody went to see local band Lakou Mizik play live, and they invited some of the members to record with them. Those players remained close at hand during the project so they could be drawn into the arrangements as needed. Browne calls singer-guitarist Paul Beaubrun, who became the bass player on all of these songs, the “glue” of the project. “As a Haitian, he speaks Creole and English and made it possible for all of us to communicate.” Then there was Habib Koité, who Browne describes as a sunrise: “For the Haitians it was like this is Mother Africa, a voice from their ancestral homeland singing to them. And he was singing in a language they didn’t know, so it was exotic to them, but it had their deep roots; it was the deep stuff.” Before they knew it, they had six songs in five days, and what had started as an idea just to do some sessions, became a record, extending the project to a second week later in the year. It was during that second session, that indie songwriter Jenny Lewis and Malian singer and guitar virtuoso Koité both recorded, and ended up collaborating on the song “Under the Supermoon.” And together they imbued the Raúl Rodríguez song “El Viajero” with an aura of transcendent mystery. Wilson called upon engineer Vira Byramji from Electric Lady Studios to join in the first week, then Trevor Spencer, Josh Tillman’s engineer, the second week to help inspire the students to become great engineers, and they conducted technology seminars for the students, who also had the opportunity to observe in the studio in small groups throughout the project. Wilson also held Q&A sessions to share such techniques as his approach to multi-miking the drum set, displaying the effects of compression on drums, and additional American-style recording techniques. Browne says with a laugh that most of his ideas are not so much moneymaking ideas, but rather money spending ideas. Browne then adds, “It was really fulfilling to be down there in a situation where we were so welcomed. These students have such dignity and a real thirst for knowledge. They were as serious as could be. Instead of working to support their larger family at home, they are being supported here in their dream to become professional engineers. To have them respond with real interest to what we were doing was very fulfilling, and it showed us all how music is the key to our own transformation. That is a pretty great feeling.” Artists for Peace and Justice Let the Rhythm Lead: Haiti Song Summit Vol. 1 is available worldwide via Arts Music Inc., a Warner Music Group Company. A short documentary and music videos from the album are available on Jackson Browne’s YouTube channel.